Over the years, when I have needed to be firm with a representative of the financial services industry (or sometimes, the legal profession, or very rarely an elected representative), I have developed a pompous and annoying little speech to introduce my objection:

“I have to tell you this [contract, disclosure, draft legislation etc] is not clear. I have two degrees in finance and economics, I have worked as a bank regulator and as a financial analyst, I have written an award winning financial newsletter for ten years and three books. I have read this carefully and I do not share your understanding of what it means, and I am not prepared to accept that this is mainly my fault”.

If you’re not planning to meet that person again, and don’t mind coming across as kind of a wanker, both of which are usually true in my case, it often works.

My point here is preparatory to an old-fashioned firendly blog debate! Between me, Andrew Gelman the political statistics expert and (by proxy) Ben Recht and Leif Weatherby, on the subject of whether Ben and Leif’s criticism of the polling industry could fairly have been described as “a Gatling Gun of truth bullets”. In summary, Andrew thinks it’s not, and might better have been described as “extreme positions, [which] other people who should know better applaud them for …which just creates incentives for further hot takes”.

I have too much of a survival instinct to get into a technical debate with Andrew Gelman about statistics! But in my view, he’s doing something familiar to me from being in the banking industry during its periodic failures and outrages; hanging everything on being technically right, the worst kind of right, while missing the big picture. Of course, the definition of a Gatling Gun is that it’s a big machine that shoots lots of bullets indiscriminately and is best used against a large and vulnerable target, so here goes…

The basic shape of the argument is that Ben and Leif wrote that the pollsters screwed up mightily by referring to the 2024 Presidential election as 50/50, too close to call, really knife edge balanced etc when it wasn’t. Andrew says this is completely unfair and gives a number of quotes to back himself up, showing that nearly all of the poll talking guys were warning that 50/50 odds doesn’t mean that it will necessarily be close, that it was entirely possible for one candidate to run through all the swing states, and so on. He also argues that a 3% error is not that bad and everyone expects too much from pollsters anyway.

And my reaction to this is the title of this post – “you can’t take it back in a disclaimer”.

There are some financial products (shared appreciation mortgages, for example, or small business interest rate swaps) which are, in my view, completely impossible to sell without creating a massive legal risk for yourself. The problem is that lots of the value in these products comes from tail probabilities of very large payouts, and it is more or less impossible, not that anyone tries very hard, to get a retail client to understand that the very large payouts in question are going to come from them. The contract might be clear, but time and again, the regulators have found that there’s a higher principle of fair dealing[1] that’s been broken, and the contract gets unwound at the expense of the bank that thought it was being really clever.

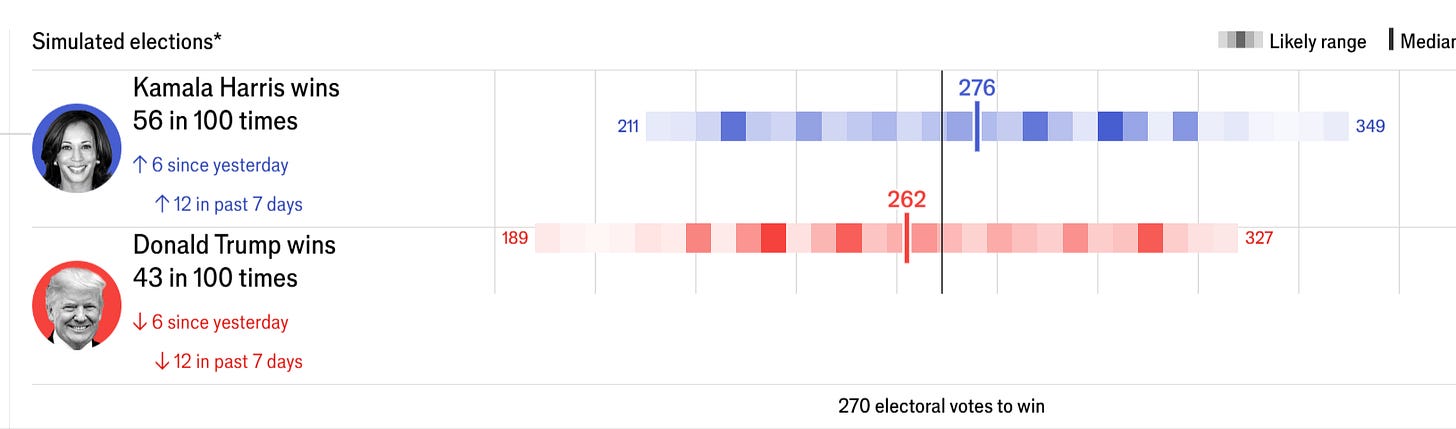

With that in mind, let’s look at some exhibits of how the election forecasts were presented. First, here’s The Economist:

I really don’t see how you could see this as communicating that a Trump landslide was a significant probability. Maybe if you stare and cross your eyes, you might notice that somewhat darker red blob on the right hand side of the line? But to me, this is quite clearly communicating the medians and (via the presentation of simulation results) the expectation. It’s not giving much idea that the distribution of outcomes was bimodal, and I don’t think it is suggesting that the actual result was within what you’d normally think of as the bounds of error.

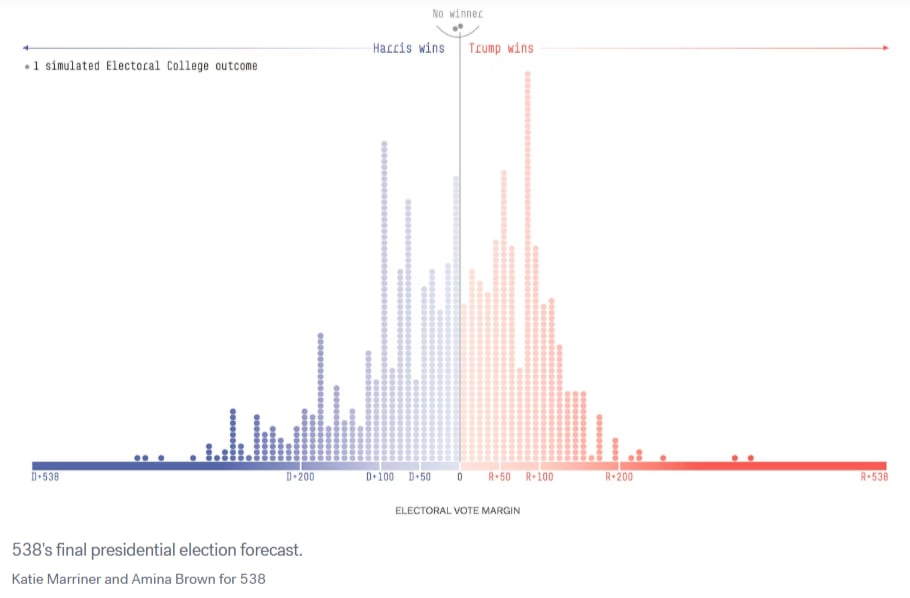

Five-thirty-eight did it quite a bit better, I think; if you know what to look for, it’s communicating a bit of bimodality in the most prominently presented picture:

Not only that, but the site does warn that “Trump and Harris, our model says, are both a normal polling error away from an Electoral College blowout” in the text.

But I think it’s very hard to communicate how likely this is, because “a normal polling error” is a difficult concept to get across. The 538 election eve post shows maps with outcomes four per cent away from their final average, and a 54/46 race is just really really different from a 50/50 one, psychologically. (I will return to this point later, but I just can’t accept that a 3% nonsampling error is pretty good; it's bigger than one third of the popular vote margins in US Presidential elections since the second world war). Unless you’ve seen the answer and know what you’re looking for, I think you’re visually much more likely to ignore the big spikes in the histogram as outliers and see a broadly normal distribution with the (eventual ex post) true outcome quite far from the centre.

How should the bimodality and uncertainty have been communicated then? I don’t know. But this is the whole problem. I am fond of wryly saying that “if something’s not worth doing, it’s not worth doing properly”. But that joke can be turned around – if something can’t be done properly, maybe it shouldn’t be done at all.

Basically, to adapt the language of a previous post, “cleaning the draining board is part of the job of washing up”. If a forecast is going to be used in public life, part of the job of forecasting is ensuring that the forecast is communicated clearly and directly, without putting excessive cognitive burden on the readers by expecting them to read and understand extremely important caveats that are placed somewhere else. At the end of the day (and in the knowledge that I’m sure this comes across just as badly as in my little speech in the introduction), I understood the pollsters to be predicting a tight election, so did Ben and so did Leif, and I’m not prepared to accept that this is all of our faults for not understanding statistics well enough or not being interested enough in politics.

Technically correct is, in this case, the worst kind of correct. The polling industry, as it exists, is putting things into the public sphere which make it worse. As well as being problematic in their own terms, the election forecasts are, in many cases, the shop window for actual policy advice. That’s really frightening for a number of reasons. First, the communication of the polling results to policymakers is likely to be at least as difficult a problem as the election forecast presentation, probably much more so. Second, the technical problems with polling are going to be worse.

As Ben and Leif point out, response rates are very low, and the efforts to reweight nonrandom samples by subjective brute force have a very significant effect on the outcome. It’s pretty easy to see why this is extremely problematic when the polling is meant to provide objective evidence of what’s popular. Andrew’s response to this issue is to say

“There are essentially no random samples of humans, whether you’re talking about political surveys, marketing surveys, public health surveys, or anything else. So if you want to say “If you can’t randomly sample, you shouldn’t survey,” you should pretty much rule out every survey that’s ever been done.”

And … yeah. Perhaps you should. Or at least, you might regard the bias and unknown error as having grown to a level where it’s acceptable for market research, but not for important policy issues. (In fact, market research has been worrying about response rates for a while, and seems to be much less hung up on traditional survey methodology than it used to be). This is a real problem – technological and social change has made it extremely difficult to get representative samples – and it might be the case that this means that survey research is no longer a viable way to find things out. That’s really unpleasant to consider, but it might be true.

It is a very very hard thing to accept that something can’t be done. Andrew Gelman’s view is a kind of harm-reduction approach; we recognise that there’s a lot of uncertainty and inaccuracy here, but people are going to demand this so let’s try to do it in as technically defensible a way as possible. Ben and Leif are taking more of a prohibitionist approach; things have got bad enough that even the best we can do is still bad, so (in their words) “the survey industry needs a tear-down …the industry is in a crisis that can’t be fixed with better regression analysis”.

Harm reduction and prohibition are, of course, tactics rather than principles; you choose the approach that you think will work best. I think I come down on the side of prohibition. (Not legal prohibition, you daft hap’worth!). The policy community has to wean itself off the use of surveys, and start using harder evidence about what is worth doing. As Ben and Leif nearly put it, the Era of the Data Guy has come to an end.

[1] In “Lying for Money”, in the context of “market crimes”, I talk about the unusual areas of the law where things are based not on common principles of justice and contract, but on the question of “what is the best rule if we want to maximise trust in this valuable institution?”