Good morning from Washington DC! This is a long one, so it might be cut off in your inbox. Also, if you’re looking for an economic holiday gift for your loved ones (or for anyone at all), and want to support local bookstores In This Economy? is a great gift!

I’m on the road again for work, traveling across Michigan, Kentucky, and DC. I was going through TSA and the woman in front of me just started open mouth coughing, like a baby does. I stared at her in wonder, imagining for a moment what it must be like to be so free from worry, and then in abject horror.

Most people are very nice. But part of being a part of a society is dealing with other people’s different internal norms. Some people open mouth cough, and that’s just how it is. My theory is that they believe collective comfort isn’t their responsibility, perhaps because they feel disconnected from the commons. It’s a form of social drift that is increasingly noticeable in public spaces (like being bent neck 90 degrees over a phone walking into walls or standing directly in the flow of pedestrian traffic).

But I think this open mouth cougher and the persistent economic malaise we see have a lot in common. Why have collective norms if you don’t trust in the systems around you? Hard work doesn’t pay off, it seems, so why shouldn’t you gamble? The institutions lie! But this YouTuber who makes Thumbnails that ask BIG QUESTION with an open mouth scream while pointing at bowl of spaghetti or whatever doesn’t lie. We don’t trust one another. As Jordan Schwartz, student chair of the Harvard Public Opinion Project said:

Gen Z is headed down a path that could threaten the future stability of American democracy and society. This is a five-alarm fire, and we need to act now if we hope to restore young people’s faith in politics, America, and each other.”

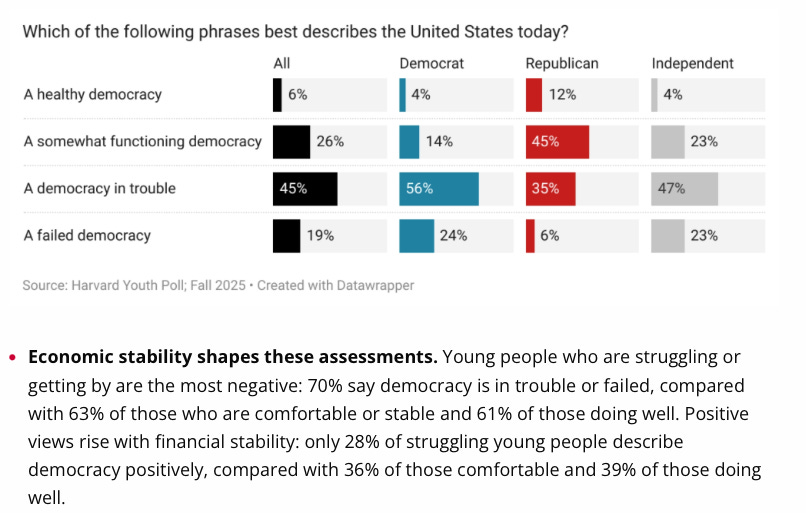

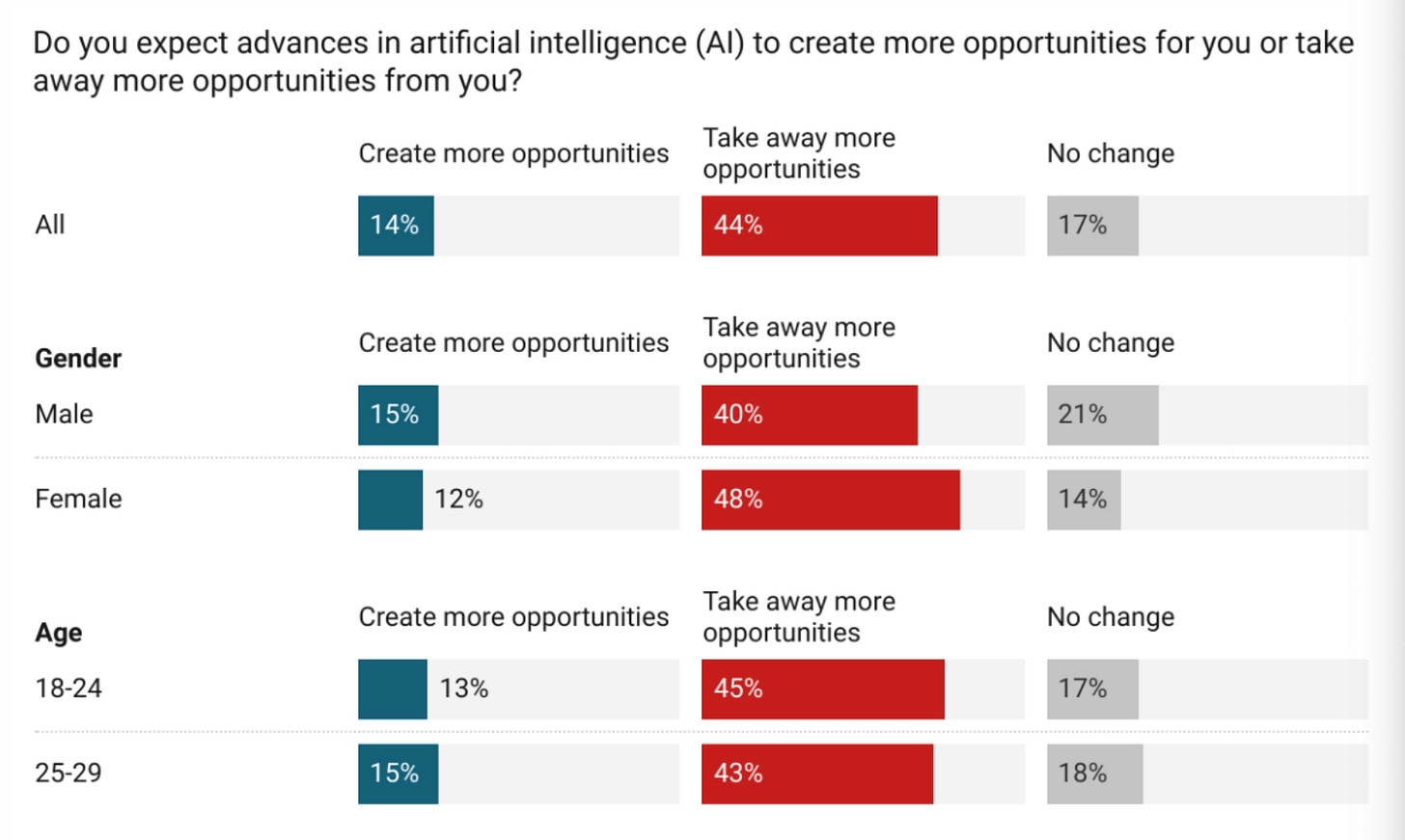

His project, the Harvard Youth Poll, surveyed over 2,000 Americans between 18- and 29-years-old on trust, politics, and AI. When asked if they think the United States is a health democracy, the split is pretty partisan, but the worry is there.

Trust between groups is collapsing too. Only 35% of young Americans believe that people with opposing views want what is best for the country. 50% see the mainstream media as a threat. And only 30% believe that they will be better off financially than their parents.

So we have three things to understand from this survey:

Worries about democracy

Worries about the economy

Worries about one another

I don’t think you can understand the economy until you understand how we talk about the economy. I think there we are dealing with a combination of (1) postpandemic adaptation and (2) the whole smartphone-induced micro-solipsism thing layered onto (3) younger generations watching objective unkindness rewarded by politics. People (understandably) are dealing with epistemic drift too, what some might call “medieval peasant brain” due to the constant influx of Internet (people are putting potatoes in their socks to draw out toxins, for example).

We’re trapped in somewhat of a compound crisis - economic deterioration plus cognitive overload creates a recursive trap where each makes the other worse and destroys the resources needed to escape.

Economic stress (Baumol’s cost disease, housing, weakening labor market) reduces our ability to think clearly, which makes us more vulnerable to scams and bad decisions and extractive markets, which then furthers the economic stress.

Economic stress + information overload erodes institutional trust

Loss of trust makes coordination impossible, which leaves problems unsolved. Unresolved problems deepen the crisis.

Right now, we’re trying to make sense of an economy inside social and cognitive environments that have shifted faster than the indicators that claim to describe them. That’s the backdrop for the Vibecession.

Note: Given that both Paul Krugman and Scott Alexander recently returned to this idea, it’s worth re-examining what the Vibecession was then and what it has become now.

The Vibecession: Then and Now

I first wrote about the Vibecession in July of 2022, at a time when inflation was coming down (but was still painfully high), the labor market was recovering, and the economy was growing. All the chips were not yet stacked on AI, no tariffs, massive infrastructure investment. On paper, things were improving.

The 2000s and 2010s had plenty of problems (plenty!) but the bottom didn’t fall out on how people felt1. There is a nostalgiacore trend on TikTok right now of teenagers now who are making up a fake 2012- dreaming of infinity scarves and third-wave coffee shops and when Instagram was about posting some daisy you saw in a field rather than a hypercompetitive algorithmic bloodbath.

There was an element of hope (it’s what Obama ran on!) and an idea of an Internet future that was Better. The Internet still had problems, but there wasn’t ragebait for income.

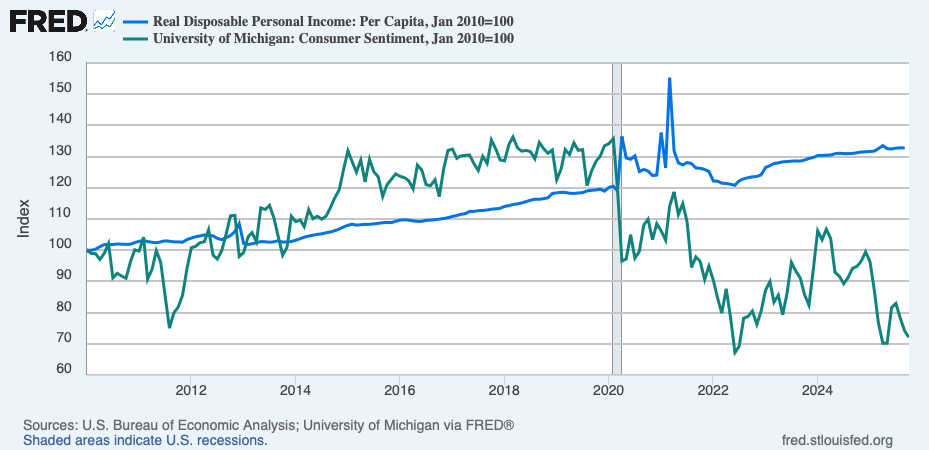

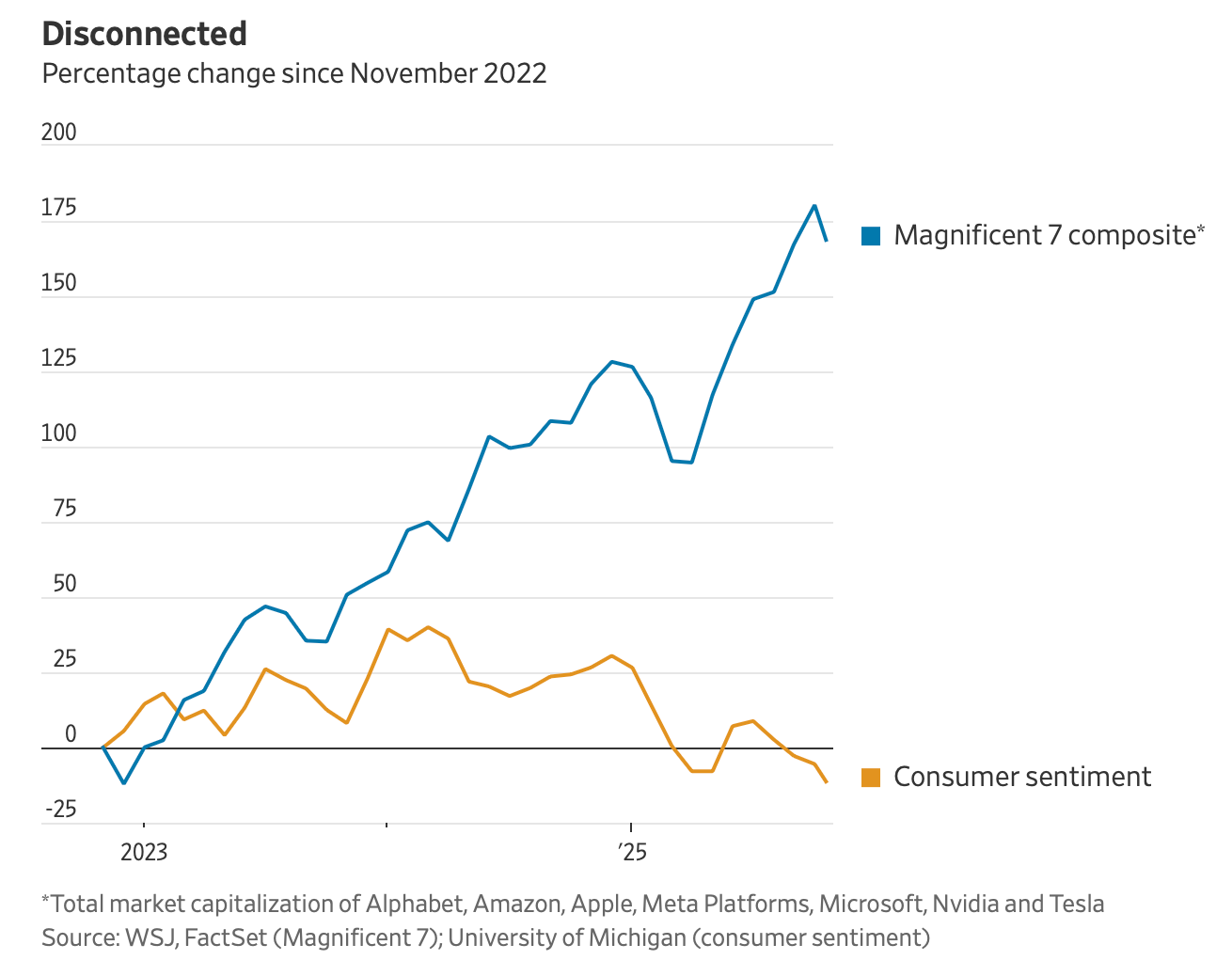

People sometimes claim “the whole last decade was a vibecession,” but the sentiment data doesn’t support that. The break is visible and sharp.

The graph below is a rough look at when the Vibecession started, showing the divergence between sentiment and economic data. Real disposable income recovered and kept rising after the pandemic shock, returning to trend. But sentiment never came back. It slid into a recession-like range (and below) and stayed there, even as economic fundamentals stabilized.

I think part of the reason was the accumulation. Again, pandemic dislocation wasn’t over. The price of everything was unstable. Stores were understaffed. Teachers (and their students) were burned out. Public messaging had shattered. Institutions felt brittle. Everyday friction of life had increased in dozens of small ways. The COVID-era spike in home prices never unwound. Mortgages locked people in place as the Fed started hiking. Rents surged. The entry path to adulthood where you move and rent and save and buy shattered for many people. No house by 2020? No house ever.

But as Dan Davies writes there might not have been any particular trigger for the Vibecession. “Vibes might be like a supercooled fluid, just waiting for a random shock to change phase.” The pandemic was the shock.

The Vibecession was early. Now, the economic data matches the sentiment, or at least matches it more than it did. We have a low-hiring environment, persistent inflation, and tremendously strange trade policy. When NBER classifies a recession, they look at three things:

Depth: How far does the economy fallen?

Diffusion: How widely is the pain spread?

Duration: How long does it all last?

When we look at the fall in consumer sentiment, it fits (crudely, at least) this definition of a recession - it’s been long-lasting, widely spread, and continuously flirts with the lowest levels in history. Kevin Gordon at Schwab calls it a Vibepression - precariously low sentiment, with GDP propped up by AI-related investment. Is an economy that is booming from AI data center build outs going to feel good to the average person? No!

But why do we have this sense of deep malaise?

Part One: Economic Deterioration

A few weeks ago, Michael Green wrote an article stating that $140k is the new poverty line, that no one can afford to participate in society. It took over the Internet in a fiery storm. There have been many rebuttals, from Tyler Cowen to Jeremy Horpedahl. But the reaction to the piece was very interesting, as John Burn Murdoch wrote about.

People overwhelmingly agreed with the article (many of the rebuttals to the rebuttals were “who cares if the math is wrong, the vibe is correct!). Both More Perfect Union and the Free Press republished it. People on both sides of the aisle, read the article and said “Well, yes, that is why things feel so bad. This is poverty. My economic pain is justified by the data now. What a relief.”

A relief to be seen in analysis. Paul Krugman, in his series on the Vibecession, argues that three concepts are poorly captured by standard economic numbers:

Economic inclusion: Can you afford to participate in society?

Security: Are you one broken tooth away from bankruptcy?

Fairness: Are you being scammed?

People need to feel like they can afford a house or a kid or a car, that they aren’t one medical bill away from ruin, and that other people aren’t cheating them. Those questions are getting harder to answer.

To the first question - the Federal Reserve cut rates yesterday, with a lot of drama and a lot of dissent. Their dual mandate - price stability and maximum employment - is under increasing pressure. Inflation is not going down to 2% (and the bond market is very worried about that). The labor market is weakening. Inequality is worsening.

There is very real economic pain. It is harder to participate in society. Young people voted for Trump to fix the economy, and now are turning against him. 18 - 29 year olds strongly disapprove of President Trump, due to his handling of the economy, according to the Yale Youth Fall 2025 poll.

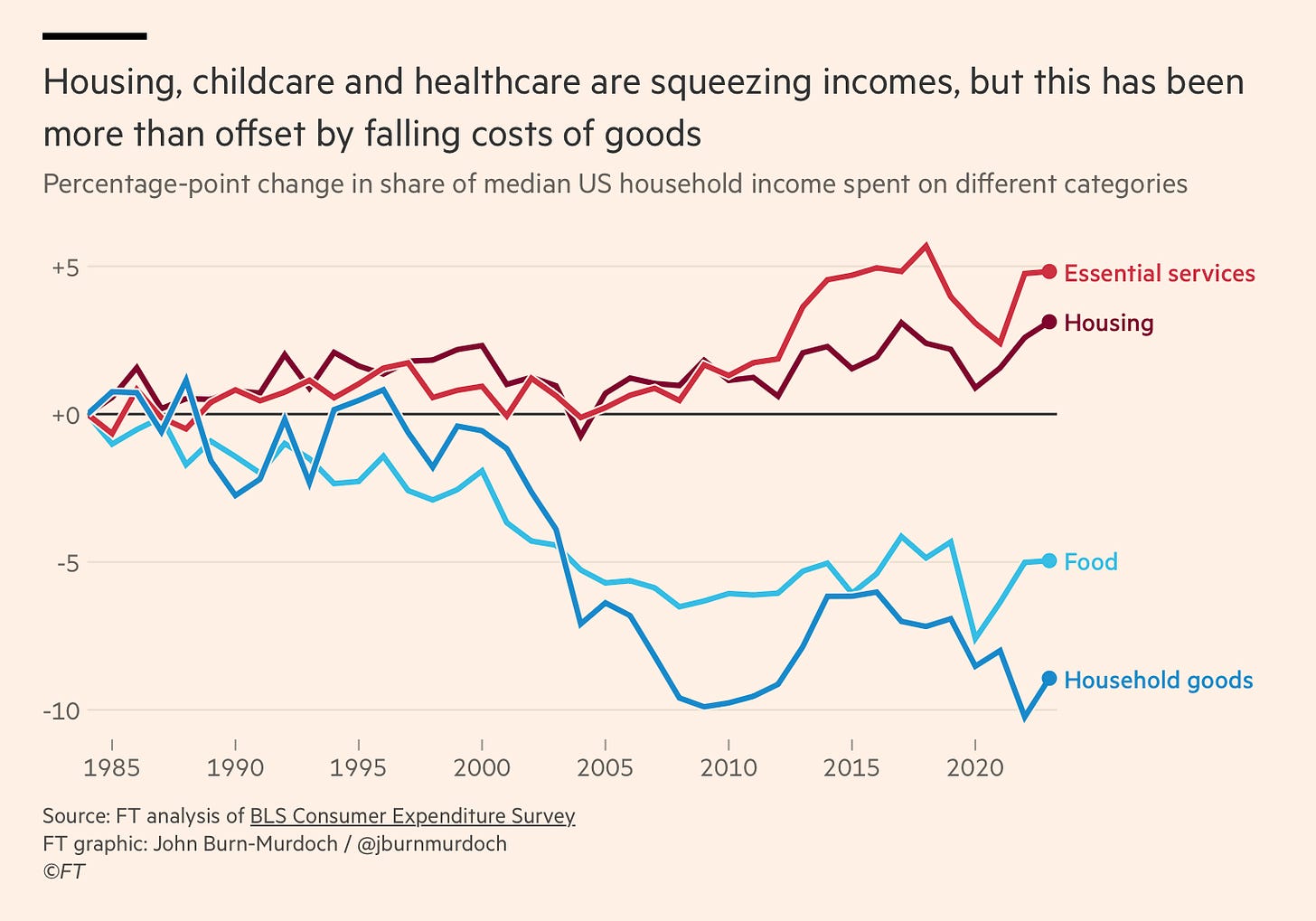

John Burn Murdoch pointed out that we are dealing with Baumol’s Cost Disease.

The same productivity growth that drives down the cost of tradeable goods causes the cost of in-person services to balloon. Wages in sectors like healthcare and education that require intensive face-to-face labour, and have slow (if any) productivity growth, are forced upwards in order to attract workers who would otherwise opt for high-paying work in more productive sectors. The result is that even if people keep consuming the exact same basket of goods and services, as living standards in their country increase they will find more and more of their spending is going on essential services.

Prosperity can make things more expensive.

For the American Prospect, Paul Starr documents the collapse of cultural affordability under Baumol, pointing out that “public elementary and secondary education, public libraries, land grant colleges with low tuition, and the 20th century’s mass media—including free, over-the-air radio and television” used to be… free. Or at least heavily subsidized. But now, support for the arts and education is being rolled back.

In practice, that means the core ingredients of a middle-class life like housing, healthcare, childcare, education, eldercare are all Baumol sectors. They’re getting more expensive faster than wages grow. You can “do everything right” and still feel underwater.

In the 20th century, we solved Baumol, sort of, by socializing or heavily subsidizing these sectors with those public schools, public libraries, state universities with low tuition, public hospitals. We made the expensive, low-productivity stuff cheaper through policy. But we’re now privatizing (or destroying or redtaping) these sectors at the exact moment we shouldn’t be. We’re asking households to absorb costs that used to be socialized. Is it any wonder that the middle class feels squeezed?

And of course, it’s going to get weirder. AI is going to make non-Baumol sectors hyper-productive. Software development, data analysis, any sort of Computer thing will become abundant and cheap, meaning that the productivity gap between scalable sectors and non-scalable sectors will becoming a gaping hole.

The second question - the government shut down this year over healthcare. The average health care premium for a family of four is $27,000 per year. Insurance premiums will increase by 10-20% next year. Many people will be a broken tooth away from bankruptcy.

The third question - we are objectively speed running a quid-pro-quo type economy, where the US, which once was a beacon of democracy, is now doing land deals with Russia, requesting that tourists give five years of social media information, threatening the independence of independent agencies, including the Fed, and ignoring anti-trust law in favor for media control.2 When you read the news and see headlines like that, it feels terrible.

So the economic fundamentals are genuinely worse for many people, especially young people trying to build a life. But economic stress alone doesn’t fully explain the depth of malaise. That’s where the cognitive dimension comes in.

Part Two: The Cognitive Overload

None of this is really new, right? The US has been drifting into a harder equilibrium for years. People have always lived through high housing costs, tight job markets, and Baumol. The difference now is that these pressures are landing on a public already stretched pretty thin cognitively and socially.

For most of human history, literacy was scarce and attention was abundant. People were what we would call “bored” most of the time, outside of work. Today, it’s the opposite - literacy is collapsing, attention is a commodity, and people are completely overloaded. Jean Twenge published a piece in the NYT titled “The Screen That Ate Your Child’s Education” writing:

In a study published in October in The Journal of Adolescence, I found that standardized test scores in math, reading and science fell significantly more in countries where students spent more time using electronic devices for leisure purposes during the school day than they did in countries where they spent less time.

And Brady Brickner-Wood writes in The Curious Notoriety of Performative Reading:

Americans read for pleasure 40% less than they did twenty years ago, and 40% of fourth graders lack basic reading comprehension […] Universities are brokering deals with companies like OpenAI to introduce chatbots into their students’ curricula and, all the while, slashing their humanities departments.

If you don’t trust any information source, you’re not going to trust economic data either. We ran this big experiment - can people have unlimited and unregulated access to millions of things that can make them lose their mind - and the answer is no, not really, it cooks the population like an egg.

The loss of education and deep reading has all sorts of downstream effects: weak basic skills, weaker media literacy, and, importantly, a collapse in trust. David Bauder’s work on teen news consumption shows that “about half of the teens surveyed believe journalists give advertisers special treatment and make up details such as quotes”.

AI is only going to complicate it more. Greg Ip’s piece The Most Joyless Tech Revolution Ever: AI Is Making Us Rich and Unhappy for the WSJ summarizes it very well. Almost 2 in 3 people are uncomfortable with AI. Only 40% of people trust the AI industry to do the right thing. We have all this technology. But we don’t trust each other and we feel terrible.

So I mean, when we think about negative sentiment, there definitely is something Computer about all of it.

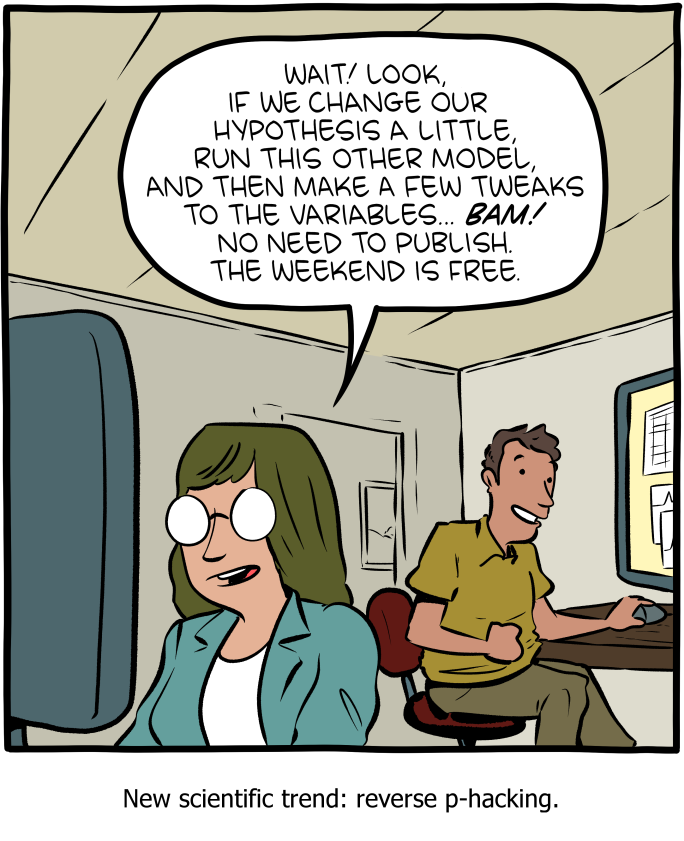

We are all collectively haunted by the Bullshit Asymmetry Principle: We are all finding that it really is 10x harder to debunk lies than it is to produce them, leading to things like ragebait as a marketing and product strategy - it’s also a great way to raise a lot of venture capital money?

Misinformation is a great way to build wealth: Twitter pays you a lot of money if you lie to a lot of people and make them very angry at you. People abroad are tapping into this money machine - logically! - and polluting US politics in a way that should probably be illegal?

Lots of people are skimming off the top of everything too, cheating the system to get ahead, to Krugman’s scam point. Every adult senses that their attention is slipping, that their thinking is flattening, that their world is flooded with noise, no neutrality, and that no institution really exists to protect them. Your brain is for sale, my guy - as your attention goes, so does your cognition, so does your sense of depth and certainty.

Confidence, optimism, and long-term thinking all require mental spaciousness. If the information environment becomes chaotic, the emotional environment will be too. And if attention is the infrastructure of democracy, that infrastructure is in disrepair.

We are seeing what happens when you outsource human learning to a screen. Now, we might learn what happens when you outsource humanness itself with the AI of it all.3 When you can’t trust any information source, you can’t trust economic data either. When attention is fractured and thinking is flattened, people become more vulnerable to the next part: extraction.

Part Three: The Extraction Economy

At the same time that the cognitive world is melting, the physical world is not maintained very well. The tremendous friction between something physical and failing (bridges, schools, labor markets) and something digital and over-optimized (LLMs, algorithms, whatever the heck people are doing with ads) is increasingly noticeable.

I am pretty tough on AI in this newsletter - and to be clear, I think it’s a tool, I think it can really make a difference for science - but AI itself is really just creating a complete downward spiral. The way Demis Hassabis talks about AI in this documentary is really important and as Linus Torvald said in a recent interview:

I’m a huge believer in AI. I’m not a huge believer in the things around AI. I find the market and marketing to be sick. There is going to be a crash.

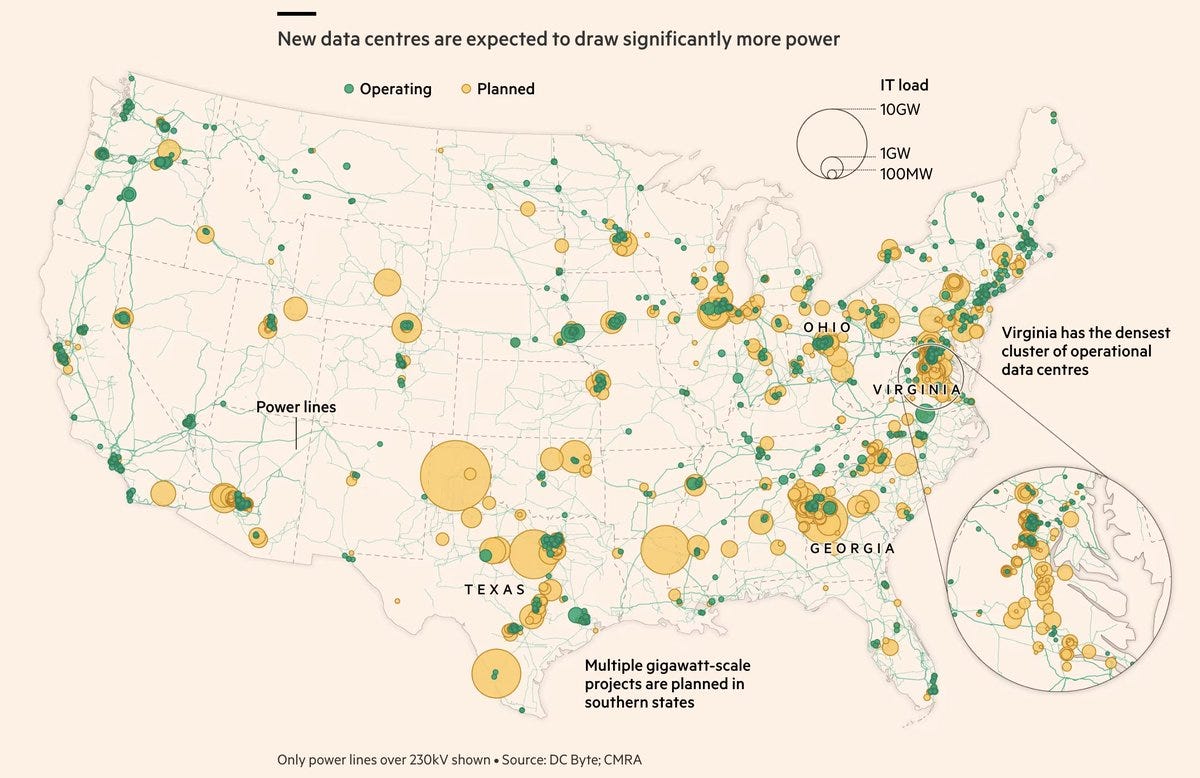

People are becoming billionaires from the data center buildout, which is driving up electricity costs and creating blackout risks. It’s an enormous physical footprint with outcomes largely invisible to ordinary people except through rising electricity bills.

The AI wars are energy wars, not compute wars. As the Financial Times wrote:

In a race between global superpowers, AI could be slowed down by decades old grid infrastructure and a failure to provide adequate capacity.

The Financial Times also reports that OpenAI’s partners have taken on $100 billion in debt to build AI compute capacity, which is scary, because debt is where things get dangerous. The dot-com bubble was mostly an equity blow up, meaning there wasn’t this web of complex who-owes-who. Once you get debt involved4, it gets very tricky very quickly.

The US has also decided to sell some of Nvidia’s best chips to China for some soybeans and a 25% kickback, which as the Department of Justice said:

The country that controls these chips will control AI technology; the country that controls AI technology will control the future.

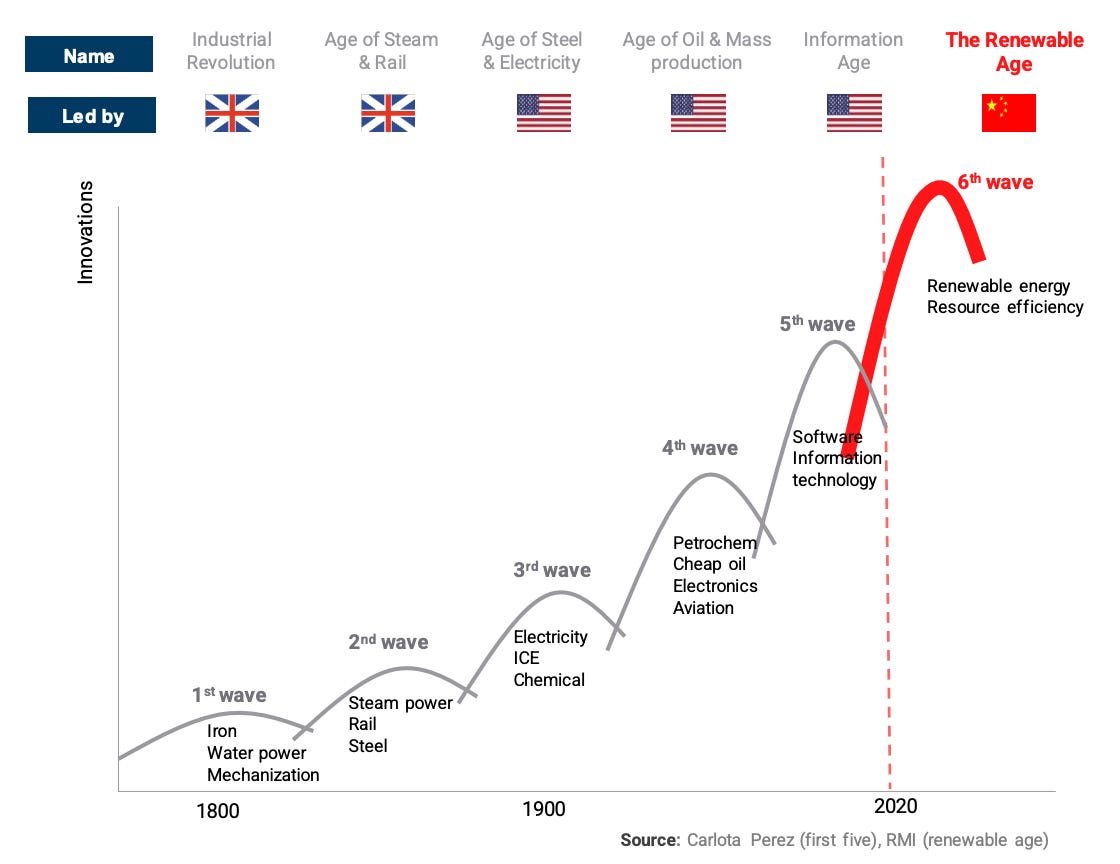

So you know, that’s fine. The Financial Times reports that the US is losing the AI race “many US companies, including Airbnb, have become fans of the “fast and cheap” Qwen” and they ask the question “can the west catch up with China?”. The chart below is really important - when we think about the future, we often think of the US as number one global superpower big guy pants, but China is investing in what is required to succeed in AI, which is energy. The US decided to do the opposite.

Barclays estimated that more than half of US GDP growth in 2025 came from AI related investment. People know that we are staking the economy on something that doesn’t really promise much other than hey :) this thing will take your job :) and it’s gonna do art now :) and maybeee make a lot of people real rich but your electricity bill (which is already flipping voters) is going to go up. And China might win. Also, it’s against the terms of service to kill yourself.

Almost all young people are very worried it’s going to take away their jobs. MIT’s Iceberg Index estimates about 12% of US wages are in jobs AI could already do cheaper today, but only 2% of that is actually being automated so far. The capability exists even if it hasn’t all been turned on yet.

How do you have trust in a system that doesn’t seem to care that much about what is going to happen to you?

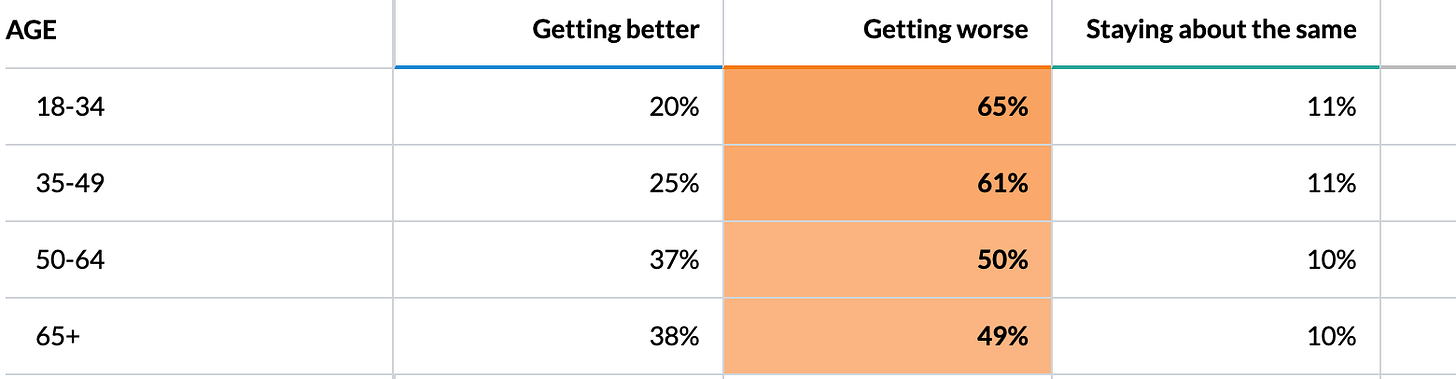

It’s likely part of the reason that almost 40% of Americans over 50 largely view the economy as “getting better” while most Americans between 18 and 49 say the economy as “getting worse”. It’s two different economies. Older people are more insulated from AI and the housing shock. Young people are staring down the barrel.

Adam Millsap wrote an interesting piece about ‘total boomer luxury communism’ which is the broad idea that older people are “hoarding opportunities and resources while the young struggle to buy a house and support the generous Social Security and Medicare benefits the richest Boomers expect.” This intergenerational intensity is only going to get worse with medically assisted longevity and the entitlement drought.

So what do people do? AI is taking the jobs, policies are increasingly designed around the older population, and everything seems murky. How does one move forward?

Gamble?

Kalshi’s co-CEO, Tarek Mansour, recently stated that the "the long term-vision is to financialize everything and create a tradable asset out of any difference in opinion.”

Financialize everything???? Every disagreement, every uncertainty, every future outcome - all of it becomes a betting line?? This is Marx’s commodity fetishism taken to its logical endpoint. It is difficult to have solidarity when every interaction is a transaction and every opinion is a tradable asset.5

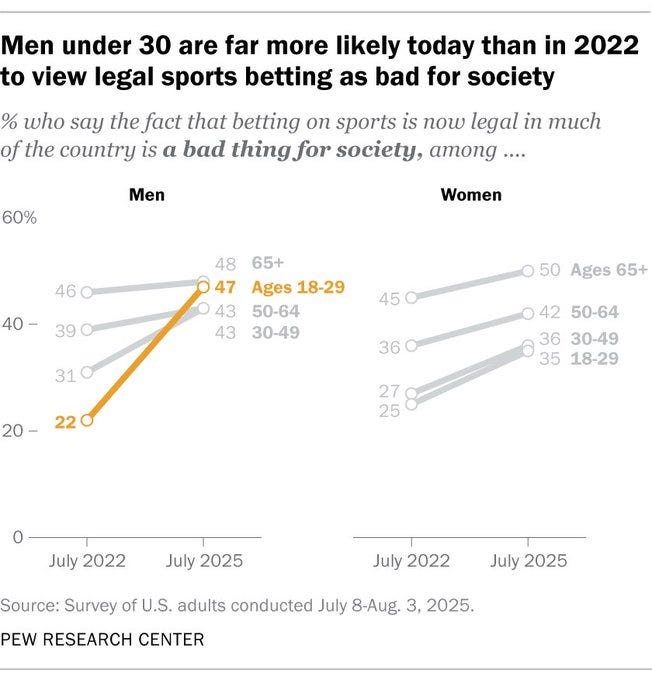

Gambling has become one of the few activities with immediate and sometimes life-changing payouts. Living near a casino increases the likelihood of becoming a problem gambler. Living inside your phone, where the casino comes to you, well, I am sure you can imagine. But no one wants this, as shown below. That’s the real bummer about the casino economy. No one wants it.

Attention being monetized, engagement being optimized, risk being financialized, everything is sort of structured like a scam - layers of middlemen extracting value as both Whitney Curry Wimbish wrote about for The American Prospect and Emily Stewart wrote about for Business Insider and no real regulation or stopguards. Some would say “well listen, clearly the market has spoken it’s preference, and that preference is that people spin the roulette wheel” but like, I don’t know.

When the labor market tightens and upward mobility stalls and when wealth is concentrated at the top and increasingly inaccessible, gambling feels like a rational response. When that’s the structure, people lose their sense of purpose and meaning (Victor Frankl, help) and that’s when problems develop.

Reduced cognitive bandwidth + extractive systems everywhere = rational economic paranoia. People sense they’re being scammed because they often are. And when the usual paths feel unpredictable, people turn to narrative ladders - online communities, aesthetic categories, etc. These become ways to make sense of uncertainty. The $140k poverty line debate fell into this landscape. The reaction was about recognition and experience and whether people’s version of the world was legible to anyone else. Not all of it is rational, but all of it exists.

When values diverge and shared baselines weaken, collective solutions become structurally impossible. Even when there’s broad consensus - no one actually wants the casino economy - we can’t coordinate to stop it because we can’t agree on what “stopping it” would look like or who should have the power to do it.

For 70 really bizarre and unusual years, America ran on a simple contract: deliver growth, and people will tolerate the rest. But on the most consistent things I hear from people across age, geography, and income from my 40 weeks on the road this year is that the basic arc of life has stopped making sense. This is anecdote, sure, but it’s what people stop to talk to me about. Their concerns. Their worries, not only about their own finances, but also about the broad future.

Part Four: Trust

So here’s where we are: caught in a compound crisis where economic stress reduces cognitive bandwidth, reduced bandwidth enables extraction, extraction deepens economic stress, stress plus overload erodes trust, loss of trust prevents coordination, coordination failure leaves problems unsolved, and unsolved problems deepen the crisis.

This isn’t a problem you solve with one policy lever. You can’t just “fix housing” or “regulate AI” or “improve media literacy” when the trap operates at the intersection of all of them. Economic deterioration and epistemic collapse are mutually reinforcing, and they’ve destroyed the institutional capacity and social trust required to address either one.

Which is bleak! But breaking that loop doesn’t require solving everything at once. It requires identifying which element is most actionable and recognizing that improving one part weakens the trap everywhere else.

Reduce economic stress directly - Make the Baumol sectors affordable again (sooo easy, I know). If people have more economic breathing room, they have more cognitive bandwidth. We all know this. More bandwidth means less vulnerability to extraction and scams. Less vulnerability means better decision-making. Better decisions mean less economic stress.

Regulate extraction directly - Ban or heavily restrict the business models that profit from confusion and cognitive overload. Kalshi wants to financialize everything? We can say no! Prediction markets on elections can be prohibited. It’s all incentives. We regulated casinos, we can regulate digital casinos.

Make AI benefits legible - Right now people experience AI as “your electricity bill is going up and eventually this will take your job.” If AI is going to drive growth, that growth needs to show up in ordinary people’s lives as tangible benefits - lower healthcare costs from diagnostic tools, cheaper goods, more time.

None of this is easy. All of it is impossibly hard. But it’s not hopeless. You don’t need to fix everything simultaneously. It requires affordability (the affordability tour just began, I hear) and state capacity and friction and sense of what it means to be human in a world full of technology and and the very simple and small task of eradicating crony capitalism and developing some sense of shared reality.

An important note - the Internet went down halfway through my cross country flight, a mere few hours after the open mouth cougher. I was typing furiously, doing all types of Very Important Work, you know, writing this newsletter. All of us were, typing, emailing, capital-S-slacking in the Dark. With no Internet, we all started to open the windows to the plane. Outside was one of the most beautiful sunsets I’ve seen. There’s something there too.

Finally, I really like this from a recent interview with Kahlil Joseph

There’s the famous story of Jimi Hendrix mastering his music for the transistor radio because that’s what the GIs listened to, so he mastered his work for FM radio. He wasn’t thinking that somebody was going to have some thousand-dollar system listening to his music. That always stuck with me, meeting people where they’re at.

Thank you.

UMich Survey of Consumers changed to web surveys instead of random digit dialing in mid-2024

Netflix and Paramount are in a bidding war for Warner Brothers, and according to the WSJ, “David Ellison offered assurances to Trump administration officials that if he bought Warner, he’d make sweeping changes to CNN, a common target of President Trump’s ire”

There is already a tremendous amount of backlash. The fact that Róisín Lanigan wrote a piece titled The Next Status Symbol is an Offline Childhood is pretty self-explainable. There are more and more pieces like P.E. Moskowitz’s The Internet is Destroying Our Memory and History, noting what the Internet has taken - and given.

Already some cracks. Applied Digital struggled to sell their bonds, offering 10% yields to attract buyers. They provide data center services to CoreWeave, which provides data center services to Nvidia & OpenAI.

Kalshi also got hit with a nationwide class action lawsuit for operating what plaintiffs claim is an “illegal sports betting platform”. The suit alleges that Kalshi was “duping” customers into believing they were betting against other consumers when they were actually betting against the house (which is Kalshi). Also, the Nevada state court has ruled that Kalshi is not exempt from state gambling regulations, which complicates their business model substantially. A Bloomberg analysis showed that Kalshi’s fees are so high that in most cases you’re better off just using FanDuel.