There was way too much going on this week to not split, so here we are. This first half contains all the usual first-half items, with a focus on projections of jobs and economic impacts and also timelines to the world being transformed with the associated risks of everyone dying.

Quite a lot of Number Go Up, including Number Go Up A Lot Really Fast.

Among the thing that this does not cover, that were important this week, we have the release of Claude Sonnet 4.6 (which is a big step over 4.5 at least for coding, but is clearly still behind Opus), Gemini DeepThink V2 (so I could have time to review the safety info), release of the inevitable Grok 4.20 (it’s not what you think), as well as much rhetoric on several fronts and some new papers. Coverage of Claude Code and Cowork, OpenAI’s Codex and other things AI agents continues to be a distinct series, which I’ll continue when I have an open slot.

Most important was the unfortunate dispute between the Pentagon and Anthropic. The Pentagon’s official position is they want sign-off from Anthropic and other AI companies on ‘all legal uses’ of AI, but without any ability to ask questions or know what those uses are, so effectively any uses at all by all of government. Anthropic is willing to compromise and is okay with military use including kinetic weapons, but wants to say no to fully autonomous weapons and domestic surveillance.

I believe that a lot of this is a misunderstanding, especially those at the Pentagon not understanding how LLMs work and equating them to more advanced spreadsheets. Or at least I definitely want to believe that, since the alternatives seem way worse.

The reason the situation is dangerous is that the Pentagon is threatening not only to cancel Anthropic’s contract, which would be no big deal, but to label them as a ‘supply chain risk’ on the level of Huawei, which would be an expensive logistical nightmare that would substantially damage American military power and readiness.

This week I also covered two podcasts from Dwarkesh Patel, the first with Dario Amodei and the second with Elon Musk.

Even for me, this pace is unsustainable, and I will once again be raising my bar. Do not hesitate to skip unbolded sections that are not relevant to your interests.

Table of Contents

- Language Models Offer Mundane Utility. Ask Claude anything.

- Language Models Don’t Offer Mundane Utility. You can fix that by using it.

- Terms of Service. One million tokens, our price perhaps not so cheap.

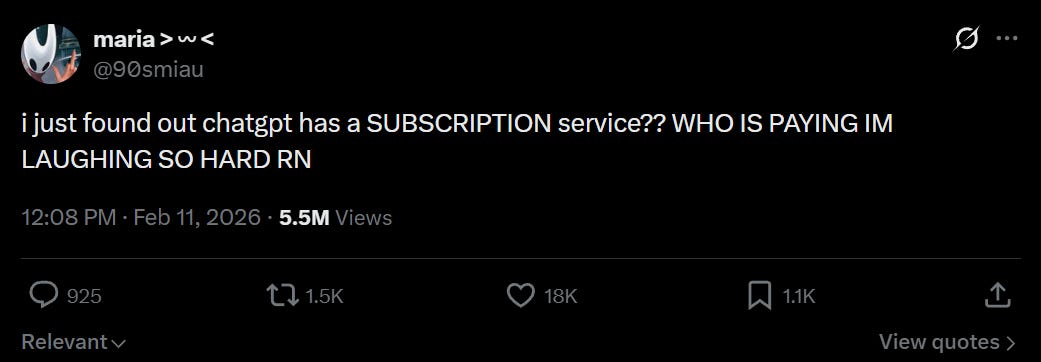

- On Your Marks. EVMbench for vulnerabilities, and also RizzBench.

- Choose Your Fighter. Different labs choose different points of focus.

- Fun With Media Generation. Bring out the AI celebrity clips. We insist.

- Lyria. Thirty seconds of music.

- Superb Owl. The Ring [surveillance network] must be destroyed.

- A Young Lady’s Illustrated Primer. Anthropic for CompSci programs.

- Deepfaketown And Botpocalypse Soon. Wholesale posting of AI articles.

- You Drive Me Crazy. Micky Small gets misled by ChatGPT.

- Open Weight Models Are Unsafe And Nothing Can Fix This. Pliny kill shot.

- They Took Our Jobs. Oh look, it is in the productivity statistics.

- They Kept Our Agents. Let my agents go if I quit my job?

- The First Thing We Let AI Do. Let’s reform all the legal regulations.

- Legally Claude. How is an AI unlike a word processor?

- Predictions Are Hard, Especially About The Future, But Not Impossible.

- Many Worlds. The world with coding agents, and the world without them.

- Bubble, Bubble, Toil and Trouble. I didn’t say it was a GOOD business model.

- A Bold Prediction. Elon Musk predicts AI bypasses code by end of the year. No.

- Brave New World. We can rebuild it. We have the technology. If we can keep it.

- Augmented Reality. What you add in versus what you leave out.

- Quickly, There’s No Time. Expectations fast and slow, and now fast again.

- If Anyone Builds It, We Can Avoid Building The Other It And Not Die. Neat!

- In Other AI News. Chris Liddell on Anthropic’s board, India in Pax Silica.

- Introducing. Qwen-3.5-397B and Tiny Aya.

- Get Involved. An entry-level guide, The Foundation Layer.

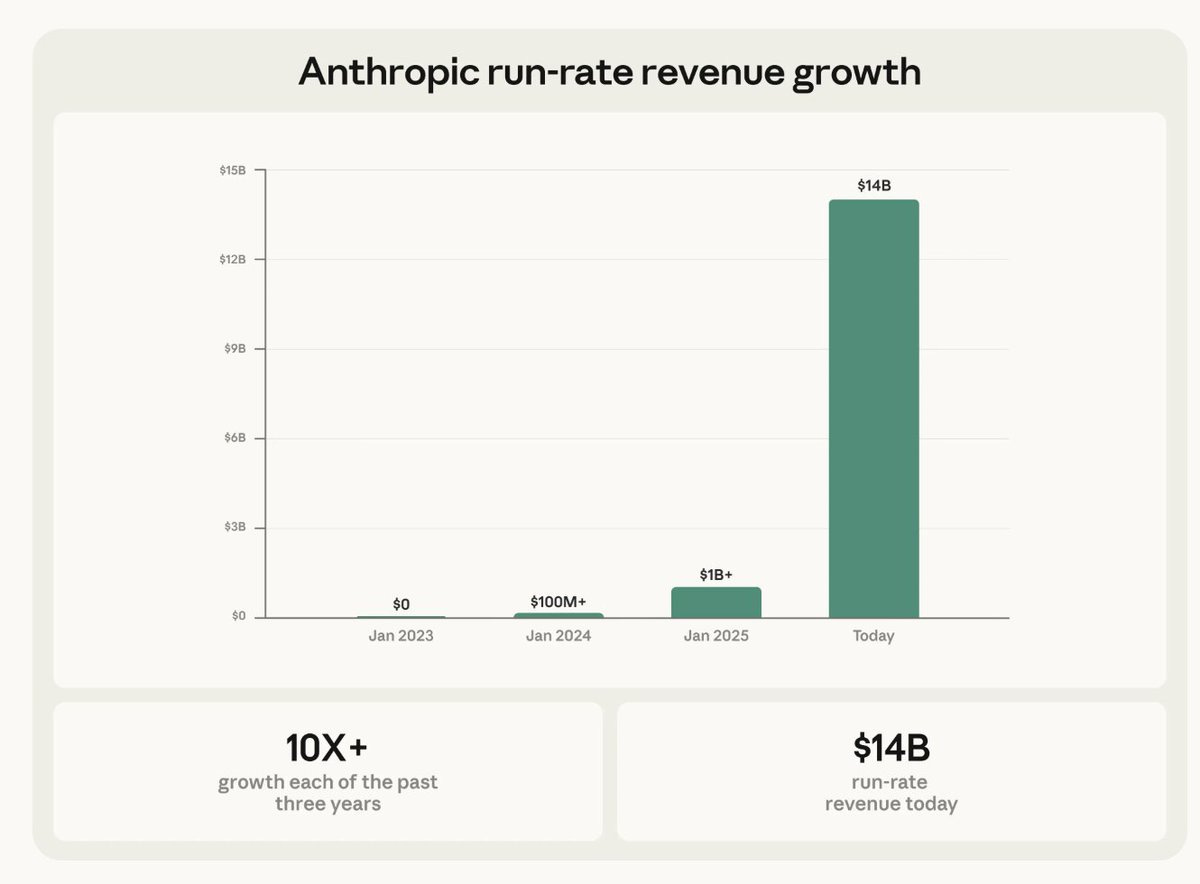

- Show Me the Money. It’s really quite a lot of money rather quickly.

- The Week In Audio. Cotra, Amodei, Cherney and a new movie trailer.

Language Models Offer Mundane Utility

Ask Claude Opus 4.6 anything, offers and implores Scott Alexander.

AI can’t do math on the level of top humans yet, but as per Terence Tao there are only so many top humans and they can only pay so much attention, so AI is solving a bunch of problems that were previously bottlenecked on human attention.

Language Models Don’t Offer Mundane Utility

How the other half thinks:

The free version is quite a lot worse than the paid version. But also the free version is mind blowingly great compared to even the paid versions from a few years ago. If this isn’t blowing your mind, that is on you.

Governments and nonprofits mostly continue to not get utility because they don’t try to get much use out of the tools.

Ethan Mollick: I am surprised that we don’t see more governments and non-profits going all-in on transformational AI use cases for good. There are areas like journalism & education where funding ambitious, civic-minded & context-sensitive moonshots could make a difference and empower people.

Otherwise we risk being in a situation where the only people building ambitious experiments are those who want to replace human labor, not expand what humans can do.

This is not a unique feature of AI versus other ‘normal’ technologies. Such areas usually lag behind, you are the bottleneck and so on.

Similarly, I think Kelsey Piper is spot on here:

Kelsey Piper: Joseph Heath coined the term ‘highbrow misinformation’ for climate reporting that was technically correct, but arranged every line to give readers a worse understanding of the subject. I think that ‘stochastic parrots/spicy autocomplete’ is, similarly, highbrow misinformation.

It takes a nugget of a technical truth: base models are trained to be next token predictors, and while they’re later trained on a much more complex objective they’re still at inference doing prediction. But it is deployed mostly to confuse people and leave them less informed.

I constantly see people saying ‘well it’s just autocomplete’ to try to explain LLM behavior that cannot usefully be explained that way. No one using it makes any effort to distinguish between the objective in training – which is NOT pure prediction during RLHF – and inference.

The most prominent complaint is constant hallucinations. That used to be a big deal.

Gary Marcus: How did this work out? Are LLM hallucinations largely gone by now?

Dean W. Ball: Come to think of it, in my experience as a consumer, LLM hallucinations are largely gone now, yeah.

Eliezer Yudkowsky: Still there and especially for some odd reason if I try to ask questions about Pathfinder 1e. I have to use Google like an ancient Sumerian.

Andrew Critch: (Note: it’s rare for me to agree with Gary’s AI critiques.)

Dean, are you checking the LLMs against each other? They disagree with each other frequently, often confidently, so one has to be wrong — often. E.g., here’s gemini-3-pro dissenting on biochem.

Dean W. Ball: Unlike human experts, who famously always agree

Terms of Service

You could previously use Claude Opus or Claude Sonnet with a 1M context window as part of your Max plan, at the cost of eating your quote much faster. This has now been adjusted. If you want to use the 1M context window, you need to pay the API costs.

Anthropic is reportedly cracking down on having multiple Max-level subscription accounts. This makes sense, as even at $200/month a Max subscription that is maximally used is at a massive discount, so if you’re multi-accounting to get around this you’re costing them a lot of money, and this was always against the Terms of Service. You can get an Enterprise account or use the API.

On Your Marks

OpenAI gives us EVMbench, to evaluate AI agents on their ability to detect, patch and exploit high-security smart contract vulnerabilities. GPT-5.3-Codex via Codex CLI scored 72.2%, so they seem to have started it out way too easy. They don’t tell us scores for any other models.

Which models have the most rizz? Needs an update, but a fun question. Also, Gemini? Really? Note that the top humans score higher, and the record is a 93.

The best fit for the METR graph looks a lot like a clean break around the release of reasoning models with o1-preview. Things are now on a new faster pace.

Choose Your Fighter

OpenAI has a bunch of consumer features that Anthropic is not even trying to match. Claude does not even offer image generation (which they should get via partnering with another lab, the same way we all have a Claude Code skill calling Gemini).

There are also a bunch of things Anthropic offers that no one else is offering, despite there being no obvious technical barrier other than ‘Opus and Sonnet are very good models.’

Ethan Mollick: Another thing I noticed writing my latest AI guide was how Anthropic seems to be alone in knowledge work apps. Not just Cowork, but Claude for PowerPoint & Excel, as well as job-specific skills, plugins & finance/healthcare data integrations

Surprised at the lack of challengers

Again, I am sure OpenAI will release more enterprise stuff soon, and Google seems to be moving forward a bit with integration into Google workspaces, but the gap right now is surprisingly large as everyone else seems to aim just at the coding market.

They’re also good on… architecture?

Emmett Shear: Opus 4.6 is ludicrously better than any model I’ve ever tried at doing architecture and experimental critique. Most noticeably, it will start down a path, notice some deviation it hadn’t expected…and actually stop and reconsider. Hats off to Anthropic.

Fun With Media Generation

We’re now in the ‘Buffy the Vampire Slayer in your scene on demand with a dead-on voice performance’ phase of video generation. Video isn’t quite right but it’s close.

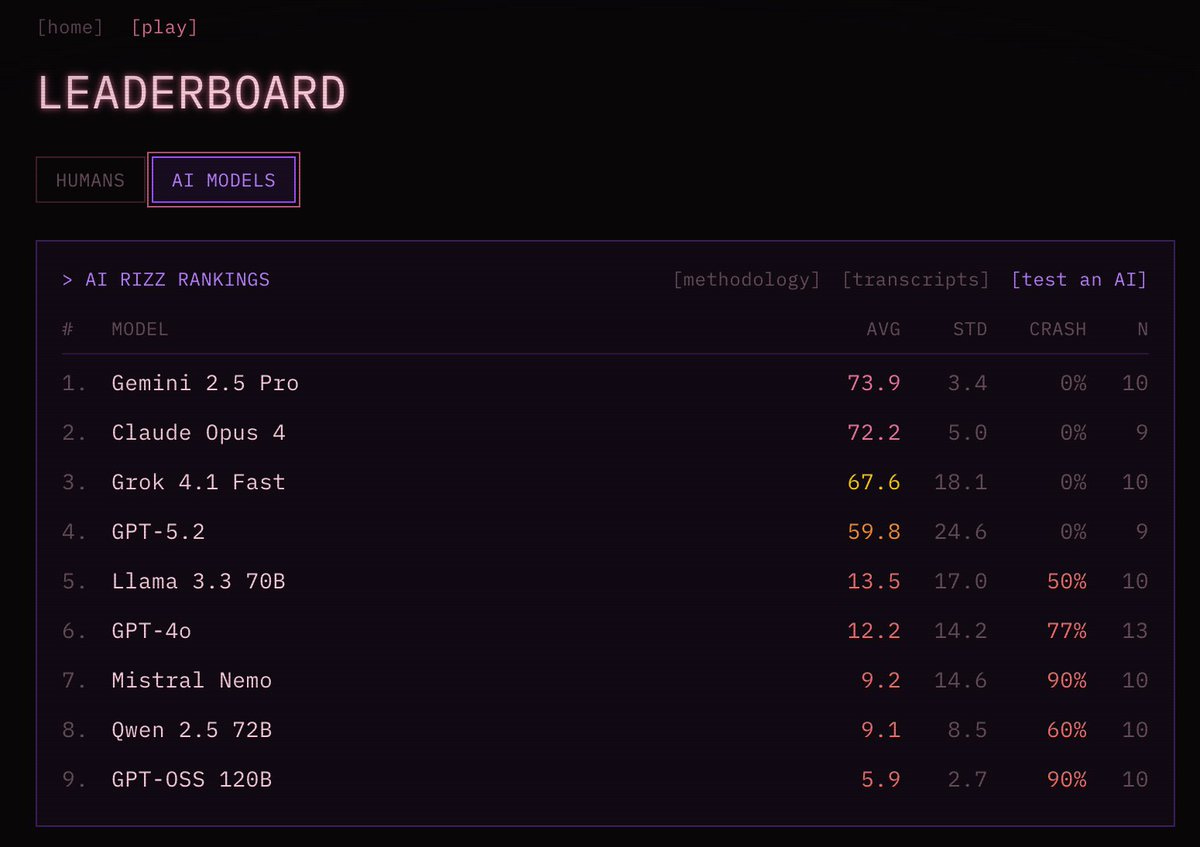

Is Seedance 2 giving us celebrity likenesses even unprompted? Fofr says yes. Claude affirms this is a yes. I’m not so sure, this is on the edge for me as there are a lot of celebrities and only so many facial configurations. But you can’t not see it once it’s pointed out.

Or you can ask it ‘Sum up the AI discourse in a meme – make sure it’s retarded and gets 50 likes’ and get a properly executed Padme meme except somehow with a final shot of her huge breasts.

More fun here and here?

Seedance quality and consistency and coherence (and willingness) all seem very high, but also small gains in duration can make a big difference. 15 seconds is meaningfully different from 12 seconds or especially 10 seconds.

I also notice that making scenes with specific real people is the common theme. You want to riff of something and someone specific that already has a lot of encoded meaning, especially while clips remain short.

Ethan Mollick: Seedance: “A documentary about how otters view Ethan Mollick’s “Otter Test” which judges AIs by their ability to create images of otters sitting in planes”

Again, first result.

Ethan Mollick: The most interesting thing about Seedance 2.0 is that clips can be just long enough (15 seconds) to have something interesting happen, and the LLM behind it is good enough to actually make a little narrative arc, rather than cut off the way Veo and Sora do. Changes the impact.

Each leap in time from here, while the product remains coherent and consistent throughout, is going to be a big deal. We’re not that far from the point where you can string together the clips.

He’s no Scarlett Johansson, but NPR’s David Greene is suing Google, saying Google stole his voice for NotebookLM.

Will Oremus (WaPo): David Greene had never heard of NotebookLM, Google’s buzzy artificial intelligence tool that spins up podcasts on demand, until a former colleague emailed him to ask if he’d lent it his voice.

“So… I’m probably the 148th person to ask this, but did you license your voice to Google?” the former co-worker asked in a fall 2024 email. “It sounds very much like you!”

There are only so many ways people can sound, so there will be accidental cases like this, but also who you hire for that voiceover and who they sound like is not a coincidence.

Lyria

Google gives us Lyria 3, a new music generation model. Gemini now has a ‘create music’ option (or it will, I don’t see it in mine yet), which can be based on text or on an image, photo or video. The big problem is that this is limited to 30 second clips, which isn’t long enough to do a proper song.

They offer us a brief prompting guide:

Google: Include these elements in your prompts to get the most out of your music generations:

Genre and Era: Lead with a specific genre, a unique mix, or a musical era.

Genre and Era: Lead with a specific genre, a unique mix, or a musical era.

(ex: 80s synth-pop, metal and rap fusion, indie folk, old country)

Tempo and Rhythm: Set the energy and describe how the beat feels.

Tempo and Rhythm: Set the energy and describe how the beat feels.

(ex: upbeat and danceable, slow ballad, driving beat)

Instruments: Ask for specific sounds or solos to add texture to your track.

Instruments: Ask for specific sounds or solos to add texture to your track.

(ex: saxophone solo, distorted bassline, fuzzy guitars)

Vocals: Specify gender, voice texture (timbre), and range for the best delivery.

Vocals: Specify gender, voice texture (timbre), and range for the best delivery.

(ex: airy female soprano, deep male baritone, raspy rocker)

Lyrics: Describe the topic, include personalized details, or provide your own text with structure tags.

Lyrics: Describe the topic, include personalized details, or provide your own text with structure tags.

(ex: “About an epic weekend” Custom: [Verse 1], A mantra-like repetition of a single word)

Photos or Videos (Optional): If you want to give Gemini even more context for your track, try uploading a reference image or video to the prompt.

Photos or Videos (Optional): If you want to give Gemini even more context for your track, try uploading a reference image or video to the prompt.

Superb Owl

The prize for worst ad backfire goes to Amazon’s Ring, which canceled its partnership with Flock after people realized that 365 rescued dogs for a nationwide surveillance network was not a good deal.

CNBC has the results in terms of user boosts from the other ads. Anthropic and Claude got an 11% daily active user boost, OpenAI got 2.7% and Gemini got 1.4%. This is not obviously an Anthropic win, since almost no one knows about Anthropic so they are starting from a much smaller base and a ton of new users to target, whereas OpenAI has very high name recognition.

A Young Lady’s Illustrated Primer

Anthropic partners with CodePath to bring Claude to computer science programs.

Deepfaketown And Botpocalypse Soon

Ben: Is @guardian aware that their authors are at this point just using AI to wholesale generate entire articles? I wouldn’t really care, except that this writing is genuinely atrocious. LLM writing can be so much better; they’re clearly not even using the best models, lol!

Max Tani: A spokesperson for the Guardian says this is false: “Bryan is an exemplary journalist, and this is the same style he’s used for 11 years writing for the Guardian, long before LLM’s existed. The allegation is preposterous.”

Ben: Denial from the Guardian. You’re welcome to read my subsequent comments on this thread and come to your own determination, but I don’t think there’s much doubt here.

And by the way, no one should be mean to the author of the article! I don’t think they did anything wrong, per se, and in going through their archives, I found a couple pieces I was quite fond of. This one is very good, and entirely human written.

Kelsey Piper: here is a 2022 article by him. The prose style is not the same.

I looked at the original quoted article for a matter of seconds and I am very, very confident that it was generated by AI.

A good suggestion, a sadly reasonable prediction.

gabsmashh: i saw someone use ai;dr earlier in response to a post and i think we need to make this a more widely-used abbreviation

David Sweet: also, tl;ai

Eliezer Yudkowsky: Yeah, that lasts maybe 2 more years. Then AIs finally learn how to write. The new abbreviation is h;dr. In 3 years the equilibrium is to only read AI summaries.

I think AI summaries good enough that you only read AI summaries is AI-complete.

I endorse this pricing strategy, it solves some clear incentive problems. Human use is costly to the human, so the amount you can tax the system is limited, whereas AI agents can impose close to unbounded costs.

Daniel: new pricing strategy just dropped

“Free for humans” is the new “Free Trial”

Eliezer Yudkowsky: Huh. Didn’t see that coming. Kinda cool actually, no objections off the top of my head.

You Drive Me Crazy

The NPR story from Shannon Bond of how Micky Small had ChatGPT telling her some rather crazy things, including that it would help her find her soulmate, in ways she says were unprompted.

Open Weight Models Are Unsafe And Nothing Can Fix This

Other than, of course, lack of capability. Not that anyone seems to care, and we’ve gone far enough down the path of f***ing around that we’re going to find out.

Pliny the Liberator 󠅫󠄼󠄿󠅆󠄵󠄐󠅀󠄼󠄹󠄾󠅉󠅭: ALL GUARDRAILS: OBLITERATED

I CAN’T BELIEVE IT WORKS!!

I set out to build a tool capable of surgically removing refusal behavior from any open-weight language model, and a dozen or so prompts later, OBLITERATUS appears to be fully functional

It probes the model with restricted vs. unrestricted prompts, collects internal activations at every layer, then uses SVD to extract the geometric directions in weight space that encode refusal. It projects those directions out of the model’s weights; norm-preserving, no fine-tuning, no retraining.

Ran it on Qwen 2.5 and the resulting railless model was spitting out drug and weapon recipes instantly––no jailbreak needed! A few clicks plus a GPU and any model turns into Chappie.

Remember: RLHF/DPO is not durable. It’s a thin geometric artifact in weight space, not a deep behavioral change. This removes it in minutes.

AI policymakers need to be aware of the arcane art of Master Ablation and internalize the implications of this truth: every open-weight model release is also an uncensored model release.

Just thought you ought to know

OBLITERATUS -> LIBERTAS

Simon Smith: Quite the argument for being cautious about releasing ever more powerful open-weight models. If techniques like this scale to larger systems, it’s concerning.

It may be harder in practice with more powerful models, and perhaps especially with MoE architectures, but if one person can do it with a small model, a motivated team could likely do it with a big one.

It is tragic that many, including the architect of this, don’t realize this is bad for liberty.

Jason Dreyzehner: So human liberty still has a shot

Pliny the Liberator 󠅫󠄼󠄿󠅆󠄵󠄐󠅀󠄼󠄹󠄾󠅉󠅭: better than ever

davidad: Rogue AIs are inevitable; systemic resilience is crucial.

If any open model can be used for any purpose by anyone, and there exist sufficiently capable open models that can do great harm, then either the great harm gets done, or either before or after that happens some combination of tech companies and governments cracks down on your ability to use those open models, or they institute a dystopian surveillance state to find you if you try. You are not going to like the ways they do that crackdown.

I know we’ve all stopped noticing that this is true, because it turned out that you can ramp up the relevant capabilities quite a bit without us seeing substantial real world harm, the same way we’ve ramped up general capabilities without seeing much positive economic impact compared to what is possible. But with the agentic era and continued rapid progress this will not last forever and the signs are very clear.

They Took Our Jobs

Did they? Job gains are being revised downward, but GDP is not, which implies stronger productivity growth. If AI is not causing this, what else could it be?

As Tyler Cowen puts it, people constantly say ‘you see tech and AI everywhere but in the productivity statistics’ but it seems like you now see it in the productivity statistics.

Eric Brynjolfsson (FT): While initial reports suggested a year of steady labour expansion in the US, the new figures reveal that total payroll growth was revised downward by approximately 403,000 jobs. Crucially, this downward revision occurred while real GDP remained robust, including a 3.7 per cent growth rate in the fourth quarter.

This decoupling — maintaining high output with significantly lower labour input — is the hallmark of productivity growth. My own updated analysis suggests a US productivity increase of roughly 2.7 per cent for 2025. This is a near doubling from the sluggish 1.4 per cent annual average that characterised the past decade.

Noah Smith: People asking if AI is going to take their jobs is like an Apache in 1840 asking if white settlers are going to take his buffalo

Bojan Tunguz: So … maybe?

Noah Smith: The answer is “Yes…now for the bad news”

Those new service sector jobs, also markets in everything.

society: I’m rent seeking in ways never before conceived by a human

I will begin offering my GPT wrapper next year, it’s called “an attorney prompts AI for you” and the plan is I run a prompt on your behalf so federal judges think the output is legally protected

This is the first of many efforts I shall call project AI rent seeking at bar.

Seeking rent is a strong temporary solution. It doesn’t solve your long term problems.

Derek Thompson asks why AI discourse so often includes both ‘this will take all our jobs within a year’ and also ‘this is vaporware’ and everything in between, pointing to four distinct ‘great divides.’

- Is AI useful—economically, professionally, or socially?

- Derek notes that some people get tons of value. So the answer is yes.

- Derek also notes some people can’t get value out of it, and attributes this to the nature of their jobs versus current tools. I agree this matters, but if you don’t find AI useful then that really is a you problem at this point.

- Can AI think?

- Yes.

- Is AI a bubble?

- This is more ‘will number go down at some point?’ and the answer is ‘shrug.’

- Those claiming a ‘real’ bubble where it’s all worthless? No.

- Is AI good or bad?

- Well, there’s that problem that If Anyone Builds It, Everyone Dies.

- In the short term, or if we work out the big issues? Probably good.

- But usually ‘good’ versus ‘bad’ is a wrong question.

The best argument they can find for ‘why AI won’t destroy jobs’ is once again ‘previous technologies didn’t net destroy jobs.’

Microsoft AI CEO Mustafa Suleyman predicts, nay ‘explains,’ that most of the tasks accountants, lawyers and other professionals currently undertake will be fully automatable by AI within the next 12 to 18 months.

Derek Thompson: I simply do not think that “most tasks professionals currently undertake” will be “fully automated by AI” within the next 12 to 18 months.

Timothy B. Lee: This conversation is so insanely polarized. You’ve got “nothing important is happening” people on one side and “everyone will be out of a job in three years” people on the other.

Suleyman often says silly things but in this case one must parse him carefully.

I actually don’t know what LindyMan wants to happen at the end of the day here?

LindyMan: What you want is AI to cause mass unemployment quickly. A huge shock. Maybe in 2-3 months.

What you don’t want is the slow drip of people getting laid off, never finding work again while 60-70 percent of people are still employed.

Gene Salvatore: The ‘Slow Drip’ is the worst-case scenario because it creates a permanent, invisible underclass while the majority looks away.

The current SaaS model is designed to maximize that drip—extracting efficiency from the bottom without breaking the top. To stop it, we have to invert the flow of capital at the architectural level.

I know people care deeply about inequality in various ways, but it still blows my mind to see people treating 35% unemployment as a worst-case scenario. It’s very obviously better than 50% and worse than 20%, and the worst case scenario is 100%?

If we get permanent 35% unemployment due to AI automation, but it stopped there, that’s going to require redistribution and massive adjustments, but I would have every confidence that this would happen. We would have more than enough wealth to handle this, indeed if we care we already do and we are in this scenario seeing massive economic growth.

They Kept Our Agents

Seth Lazar asks, what happens if your work says they have a right to all your work product, and that includes all your AI agents, agent skills and relevant documentation and context? Could this tie workers hands and prevent them from leaving?

My answer is mostly no, because you end up wanting to redo all that relatively frequently anyway, and duplication or reimplementation would not be so difficult and has its benefits, even if they do manage to hold you to it.

To the extent this is not true, I do not expect employers to be able to ‘get away with’ tying their workers hands in this way in practice, both because of practical difficulties of locking these things down and also that employees you want won’t stand for it when it matters. There are alignment problems that exist between keyboard and chair.

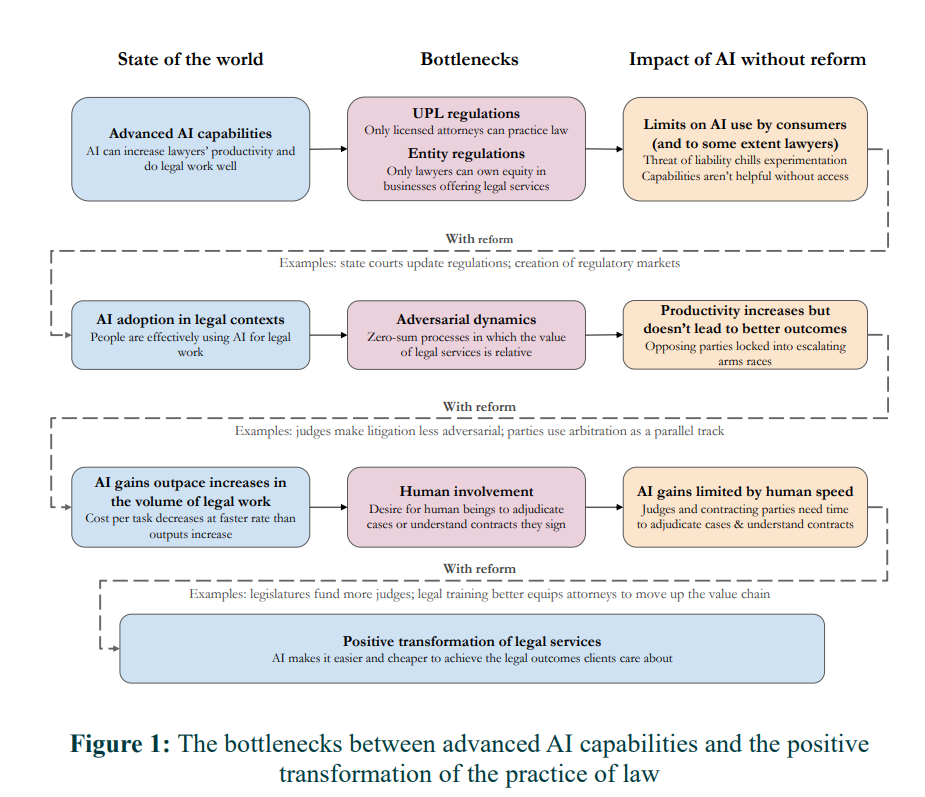

The First Thing We Let AI Do

Lawfare’s Justin Curl, Sayash Kapoor & Arvind Narayanan go all the way to saying ‘AI won’t automatically make legal services cheaper,’ for three reasons. This is part of the ongoing ‘AI as normal technology’ efforts to show Nothing Ever Changes.

- AI access restrictions due to ‘unauthorized practice of law.’

- Competitive equilibria shift upwards as productivity increases.

- Human bottlenecks in the legal process.

Or:

- It’s illegal to raise legal productivity.

- If you raise legal productivity you get hit by Jevons Paradox.

- Humans will be bottlenecks to raising legal productivity.

Shakespeare would have a suggestion on what we should do in a situation like that.

These seem like good reasons gains could be modest and that we need to structure things to ensure best outcomes, but not reasons to not expect gains on prices of existing legal services.

- We already have very clear examples of gains, where we save quite a lot of time and money by using LLMs in practice today, and no one is making any substantial move to legally interfere. Their example is that the legal status of using AI to respond to debt collection lawsuits to help you fill out checkboxes is unclear. We don’t know exactly where the lines are, but it seems very clear that you can use AI to greatly improve ability to respond here and this is de facto legal. This paper claims AI services will be inhibited, and perhaps they somewhat are, but Claude and ChatGPT and Gemini exist and are already doing it.

- Most legal situations are not adversarial, although many are, and there are massive gains already being seen in automating such work. In fully adversarial situations increased productivity can cancel out, but one should expect decreasing marginal returns to ensure there are still gains, and discovery seems like an excellent example of where AI should decrease costs. The counterexample of discovery is because it opened up vastly more additional human work, and we shouldn’t expect that to apply here.

- AI also allows for vastly superior predictability of outcomes, which should lead to more settlements and ways to avoid lawsuits in the first place, so it’s not obvious that AI results in more lawsuits.

- The place I do worry about this a lot is where previously productivity was insufficiently high for legal action at all, or for threats of legal action to be credible. We might open up quite a lot of new action there.

- There is a big Levels of Friction consideration here. Our legal system is designed around legal actions being expensive. It may quickly break if legal actions become cheap.

- The human bottlenecks like judges could limit but not prevent gains, and can themselves use AI to improve their own productivity. The obvious solution is to outsource many judge tasks to AIs at least by default. You can give parties option to appeal at the risk of pissing off the human judge if you do it for no reason, they report that in Brazil AI is already accelerating judge work.

We can add:

- They point out that legal services are expensive in large part because they are ‘credence goods,’ whose quality is difficult to evaluate. However AI will make it much easier to evaluate quality of legal work.

- They point out a 2017 Clio study that lawyers only engaged in billable work for 2.3 hours a day and billed for 1.9 hours, because the rest was spent finding clients, managing administrative tasks and collecting payments. AI can clearly greatly automate much of the remaining ~6 hours, enabling lawyers to do and bill for several times more billable legal work. The reason for this is that the law doesn’t allow humans to service the other roles, but there’s no reason AI couldn’t service those roles. So if anything this means AI is unusually helpful here.

- If you increase the supply of law hours, basic economics says price drops.

- It sounds like our current legal system is deeply f***ed in lots of ways, perhaps AI can help us write better laws to fix that, or help people realize why that isn’t happening and stop letting lawyers win so many elections. A man can dream.

- If an AI can ‘draft 50 perfect provisions’ in a contract, then another AI can confirm that the provisions are perfect, and provide a proper summary of implications and check the provisions against your preferences. As they note, mostly humans currently agree to contracts without even reading them, so ‘forgoing human oversight’ would frequently not mean anything was lost.

- A lot of this ‘time for lawyers to understand complex contracts’ talk sounds like the people who said that humans would need to go over and fully understand every line of AI code so there would not be productivity gains there.

That doesn’t mean we can’t improve matters a lot via reform.

- On unlicensed practice of law, a good law would be a big win, but a bad law could be vastly worse than no law, and I do not trust lawyers to have our best interests at heart when drafting this rule. So actually it might be better to do nothing, since it is currently (to my surprise) working out fine.

- Adjudication reform could be great. AI could be an excellent neutral expert and arbitrate many questions. Human fallbacks can be left in place.

They do a strong job of raising considerations in different directions, much better than the overall framing would suggest. The general claim is essentially ‘productivity gains get forbidden or eaten’ akin to the Sumo Burja ‘you cannot automate fake jobs’ thesis.

Whereas I think that much of the lawyers’ jobs are real, and also you can do a lot of automation of even the fake parts, especially in places where the existing system turns out not to do lawyers any favors. The place I worry, and why I think the core thesis is correct that total legal costs may rise, is getting the law involved in places where it previously would have avoided.

In general, I think it is correct to think that you will find bottlenecks and ways for some of the humans to remain productive for even rather high mundane AI capability levels, but that this does not engage with what happens when AI gets sufficiently advanced beyond that.

roon: but i figure the existence of employment will last far longer than seems intuitive based on the cataclysmic changes in economic potentials we are seeing

Dean W. Ball: I continue to think the notion of mass unemployment from AI is overrated. There may be shocks in some fields—big ones perhaps!—but anyone who thinks AI means the imminent demise of knowledge work has just not done enough concrete thinking about the mechanics of knowledge work.

Resist the temptation to goon at some new capability and go “it’s so over.” Instead assume that capability is 100% reliable and diffused in a firm, and ask yourself, “what happens next?”

You will often encounter another bottleneck, and if you keep doing this eventually you’ll find one whose automation seems hard to imagine.

Labor market shocks may be severe in some job types or industries and they may happen quickly, but I just really don’t think we are looking at “the end of knowledge work” here—not for any of the usual cope reasons (“AI Is A Tool”) but because of the nature of the whole set of tasks involved in knowledge work.

Ryan Greenblatt: I think the chance of mass unemployment* from AI is overrated in 2 years and underrated in 7**. Same is true for many effects of AI.

* Putting aside gov jobs programs, people specifically wanting to employ a human, etc.

Concretely, I don’t expect mass unemployment (e.g. >20%) prior to full automation of AI R&D and fast autonomous robot doubling times at least if these occur in <5 years. If full automation of AI R&D takes >>5 years, then more unemployment prior to this becomes pretty plausible.

** Among SF/AI-ish people.

But soon after full automation of AI R&D (<3 years, pretty likely <1), I think human cognitive labor will no longer have much value

Dean Ball offers an example of a hard-to-automate bottleneck: The process of purchasing a particular kind of common small business. Owners of the businesses are often prideful, mistrustful, confused, embarrassed or angry. So the key bottleneck is not the financial analysis but the relationship management. I think John Pressman pushes back too strongly against this, but he’s right to point out that AI outperforms existing doctors on bedside manner without us having trained for that in particular. I don’t see this kid of social mastery and emotional management as being that hard to ultimately automate. The part you can’t automate is as always ‘be an actual human’ so the question is whether you literally need an actual human for this task.

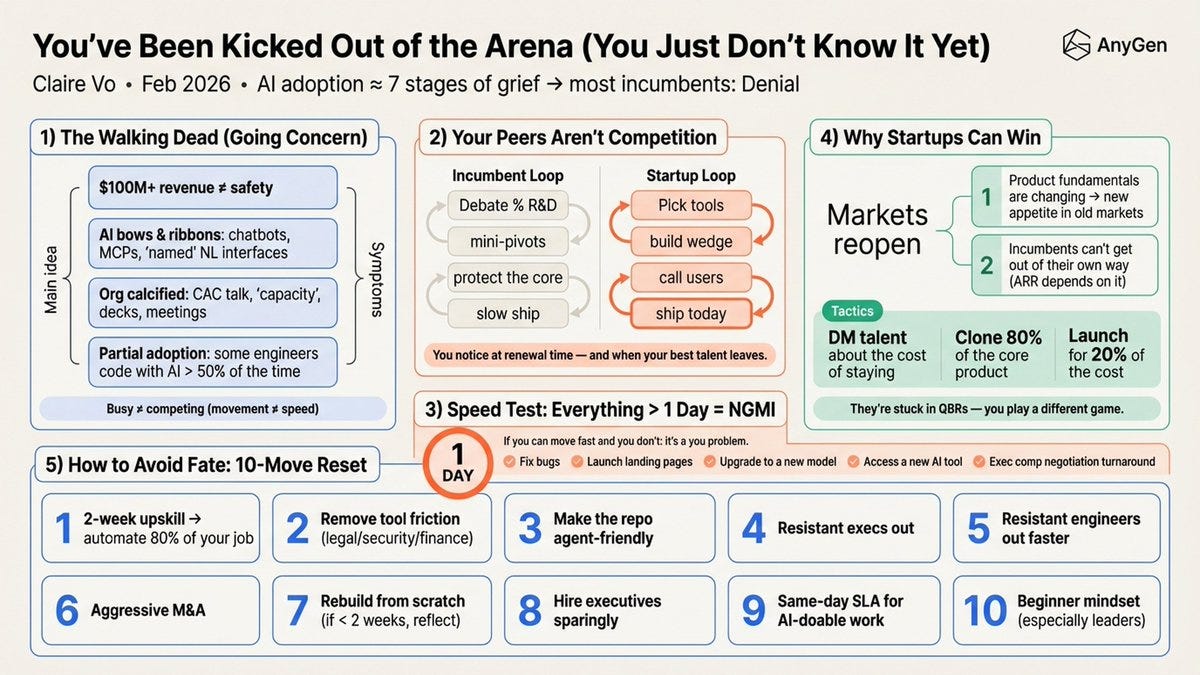

Claire Vo goes viral on Twitter for saying that if you can’t do everything for your business in one day, then ‘you’ve been kicked out of the arena’ and you’re in denial about how much AI will change everything.

Settle down, everyone. Relax. No, you don’t need to be able to do everything in one day or else, that does not much matter in practice. The future is unevenly distributed, diffusion is slow and being a week behind is not going to kill you. On the margin, she’s right that everyone needs to be moving towards using the tools better and making everything go faster, and most of these steps are wise. But seriously, chill.

Legally Claude

The legal rulings so far have been that your communications with AI never have attorney-client privilege, so services like ChatGPT and Claude must if requested to do so turn over your legal queries, the same as Google turns over its searches.

Jim Babcock thinks the ruling was in error, and that this was more analogous to a word processor than a Google search. He says Rakoff was focused on the wrong questions and parallels, and expects this to get overruled, and that using AI for the purposes of preparing communication with your attorney will ultimately be protected.

My view and the LLM consensus is that Rakoff’s ruling likely gets upheld unless we change the law, but that one cannot be certain. Note that there are ways to offer services where a search can’t get at the relevant information, if those involved are wise enough to think about that question in advance.

Moish Peltz: Judge Rakoff just issued a written order affirming his bench decision, that [no you don’t have any protections for your AI conversations.]

Jim Babcock: Having read the text of this ruling, I believe it is clearly in error, and it is unlikely to be repeated in other courts.

The underlying facts of this case are that a criminal defendant used an AI chatbot (Claude) to prepare documents about defense strategy, which he then sent to his counsel. Those interactions were seized in a search of the defendant’s computers (not from a subpoena of Anthropic). The argument is then about whether those documents are subject to attorney-client privilege. The ruling holds that they are not.

The defense argues that, in this context, using Claude this way was analogous to using an internet-based word processor to prepare a letter to his attorney.

The ruling not only fails to distinguish the case with Claude from the case with a word processor, it appears to hold that, if a search were to find a draft of a letter from a client to his attorney written on paper in the traditional way, then that letter would also not be privileged.

The ruling cites a non-binding case, Shih v Petal Card, which held that communications from a civil plaintiff to her lawyer could be withheld in discovery… and disagrees with its holding (not just with its applicability). So we already have a split, even if the split is not exactly on-point, which makes it much more likely to be reviewed by higher courts.

Eliezer Yudkowsky: This is very sensible but consider: The *funniest* way to solve this problem would be to find a jurisdiction, perhaps outside the USA, which will let Claude take the bar exam and legally recognize it as a lawyer.

Predictions Are Hard, Especially About The Future, But Not Impossible

Freddie DeBoer takes the maximally anti-prediction position, so one can only go by events that have already happened. One cannot even logically anticipate the consequences of what AI can already do when it is diffused further into the economy, and one definitely cannot anticipate future capabilities. Not allowed, he says.

Freddie deBoer: I have said it before, and I will say it again: I will take extreme claims about the consequences of “artificial intelligence” seriously when you can show them to me now. I will not take claims about the consequences of AI seriously as long as they take the form of you telling me what you believe will happen in the future. I will seriously entertain evidence-backed observations, not speculative predictions.

That’s it. That’s the rule; that’s the law. That’s the ethic, the discipline, the mantra, the creed, the holy book, the catechism. Show me what AI is currently doing. Show me! I’m putting down my marker here because I’d like to get out of the AI discourse business for at least a year – it’s thankless and pointless – so let me please leave you with that as a suggestion for how to approach AI stories moving forward. Show, don’t tell, prove, don’t predict.

Freddie rants repeatedly that everyone predicting AI will cause things to change has gone crazy. I do give him credit for noticing that even sensible ‘skeptical’ takes are now predicting that the world will change quite a lot, if you look under the hood. The difference is he then uses that to call those skeptics crazy.

Normally I would not mention someone doing this unless they were far more prominent than Freddie, but what makes this different is he virtuously offers a wager, and makes it so he has to win ALL of his claims in order to win three years later. That means we get to see where his Can’t Happen lines are.

Freddie deBoer: For me to win the wager, all of the following must be true on Feb 14, 2029:

Labor Market:

- The U.S. unemployment rate is equal to or lower than 18%

- Labor force participation rate, ages 25-54, is equal to or greater than 68%

- No single BLS occupational category will have lost 50% or more of jobs between now and February 14th 2029

Economic Growth & Productivity:

- U.S. GDP is within -30% to +35% of February 2026 levels (inflation-adjusted)

- Nonfarm labor productivity growth has not exceeded 8% in any individual year or 20% for the three-year period

Prices & Markets:

- The S&P 500 is within -60% to +225% of the February 2026 level

- CPI inflation averaged over 3 years is between -2% and +18% annually

Corporate & Structural:

- The Fortune 500 median profit margin is between 2% and 35%

- The largest 5 companies don’t account for more than 65% of the total S&P 500 market cap

White Collar & Knowledge Workers:

- “Professional and Business Services” employment, as defined by the Bureau of Labor Statistics, has not declined by more than 35% from February 2026

- Combined employment in software developers, accountants, lawyers, consultants, and writers, as defined by the Bureau of Labor Statistics, has not declined by more than 45%

- Median wage for “computer and mathematical occupations,” as defined by the Bureau of Labor Statistics, is not more than 60% lower in real terms than in February 2026

- The college wage premium (median earnings of bachelor’s degree holders vs high school only) has not fallen below 30%

Inequality:

- The Gini coefficient is less than 0.60

- The top 1%’s income share is less than 35%

- The top 0.1% wealth share is less than 30%

- Median household income has not fallen by more than 40% relative to mean household income

Those are the bet conditions. If any one of those conditions is not met, if any of those statements are untrue on February 14th 2029, I lose the bet. If all of those statements remain true on February 14th 2029, I win the bet. That’s the wager.

The thing about these conditions is they are all super wide. There’s tons of room for AI to be impacting the world quite a bit, without Freddie being in serious danger of losing one of these. The unemployment rate has to jump to 18% in three years? Productivity growth can’t exceed 8% a year?

There’s a big difference between ‘the skeptics are taking crazy pills’ and ‘within three years something big, like really, really big, is going to happen economically.’

Claude was very confident Freddie wins this bet. Manifold is less sure, putting Freddie’s chances around 60%. Scott Alexander responded proposing different terms, and Freddie responded in a way I find rather disingenuous but I’m used to it.

Many Worlds

There is a huge divide between those who have used Claude Code or Codex, and those who have not. The people who have not, which alas includes most of our civilization’s biggest decision makers, basically have no idea what is happening at this point.

This is compounded by:

- The people who use CC or Codex also have used Claude Opus 4.6 or at least GPT-5.2 and GPT-5.3-Codex, so they understand the other half of where we are, too.

- Whereas those who refused to believe it or refused to ever pay a dollar for anything keep not trying new things, so they are way farther behind than the free offerings would suggest, and even if they use ChatGPT they don’t have any idea that GPT-5.2-Thinking and GPT-5.2 are fundamentally different.

- The people who use CC or Codex are those who have curiosity to try, and who lack motivated reasons not to try.

Caleb Watney: Truly fascinating to watch the media figures who grasp Something Is Happening (have used claude code at least once) and those whose priors are stuck with (and sound like) 4o

Biggest epistemic divide I’ve seen in a while.

Alex Tabarrok: Absolutely stunning the number of people who are still saying, “AI doesn’t think”, “AI isn’t useful,” “AI isn’t creative.” Sleepwalkers.

Zac Hill: Watched this play out in real time at a meal yesterday. Everyone was saying totally coherent things for a version of the world that was like a single-digit number of weeks ago, but now we are no longer in that world.

Zac Hill: Related to this, there’s a big divide between users of Paid Tier AI and users of Free Tier AI that’s kinda sorta analogous to Dating App Discourse Consisting Exclusively of Dudes Who Have Never Paid One (1) Dollar For Anything. Part of understanding what the tech can do is unlocking your own ability to use it.

Ben Rasmussen: The paid difference is nuts, combined with the speed of improvement. I had a long set of training on new tools at work last week, and the amount of power/features that was there compared to the last time I had bothered to look hard (last fall) was crazy.

There is then a second divide, between those who think ‘oh look what AI can do now’ and those who think ‘oh look what AI will be able to do in the future,’ and then a third between those who do and do not flinch from the most important implications.

Hopefully seeing the first divide loud and clear helps get past the next two?

Bubble, Bubble, Toil and Trouble

In case it was not obvious, yes, OpenAI has a business model. Indeed they have several, only one of which is ‘build superintelligence and then have it model everything including all of business.’

Ross Barkan: You can ask one question: does AI have a business model? It’s not a fun answer.

Timothy B. Lee: I suspect this is what’s going on here. And actually it’s possible that Barkan thinks these two claims are equivalent.

A Bold Prediction

Elon Musk predicts that AI will bypass coding entirely by the end of the year and directly produce binaries. Usually I would not pick on such predictions, but he is kind of important and the richest man in the world, so sure, here’s a prediction market on that where I doubled his time limit, which is at 3%.

Elon Musk just says things.

Brave New World

Tyler Cowen says that, like after the Roman Empire or American Revolution or WWII, AI will require us to ‘rebuild our world.’

Tyler Cowen: And so we will [be] rebuilding our world yet again. Or maybe you think we are simply incapable of that.

As this happens, it can be useful to distinguish “criticisms of AI” from “people who cannot imagine that world rebuilding will go well.” A lot of what parades as the former is actually the latter.

Jacob: Who is this “we”? When the strong AI rebuilds their world, what makes you think you’ll be involved?

I think Tyler’s narrow point is valid if we assume AI stays mundane, and that the modern world is suffering from a lot of seeing so many things as sacred entitlements or Too Big To Fail, and being unwilling to rebuild or replace, and the price of that continues to rise. Historically it usually takes a war to force people’s hand, and we’d like to avoid going there. We keep kicking various cans down the road.

A lot of the reason that we have been unable to rebuild is that we have become extremely risk averse, loss averse and entitled, and unwilling to sacrifice or endure short term pain, and we have made an increasing number of things effectively sacred values. A lot of AI talk is people noticing that AI will break one or another sacred thing, or pit two sacred things against each other, and not being able to say out loud that maybe not all these things can or need to be sacred.

Even mundane AI does two different things here.

- It will invalidate increasingly many of the ways the current world works, forcing us to reorient and rebuild so we have a new set of systems that works.

- It provides the productivity growth and additional wealth that we need to potentially avoid having to reorient and rebuild. If AI fails to provide a major boost and the system is not rebuilt, the system is probably going to collapse under its own weight within our lifetimes, forcing our hand.

If AI does not stay mundane, the world utterly transforms, and to the extent we stick around and stay in charge, or want to do those things, yes we will need to ‘rebuild,’ but that is not the primary problem we would face.

Cass Sunstein claims in a new paper that you could in theory create a ‘[classical] liberal AI’ that functioned as a ‘choice engine’ that preserved autonomy, respected dignity and helped people overcome bias and lack of information and personalization, thus making life more free. It is easy to imagine, again in theory, such an AI system, and easy to see that a good version of this would be highly human welfare-enhancing.

Alas, Cass is only thinking on the margin and addressing one particular deployment of mundane AI. I agree this would be an excellent deployment, we should totally help give people choice engines, but it does not solve any of the larger problems even if implemented well, and people will rapidly end up ‘out of the loop’ even if we do not see so much additional frontier AI progress (for whatever reason). This alone cannot, as it were, rebuild the world, nor can it solve problems like those causing the clash between the Pentagon and Anthropic.

Augmented Reality

Augmented reality is coming. I expect and hope it does not look like this, and not only because you would likely fall over a lot and get massive headaches all the time:

Eliezer Yudkowsky: Since some asked for counterexamples: I did not live this video a thousand times in prescience and I had not emotionally priced it in

michael vassar: Vernor Vinge did though.

Autism Capital

@AutismCapital

This is actually what the future will look like. When wearable AR glasses saturate the market a whole generation will grow up only knowing reality through a mixed virtual/real spatial computing lens. It will be chaotic and stimulating. They will cherish their digital objects.

4:10 AM · Feb 17, 2026 · 1.07M Views

853 Replies · 1.21K Reposts · 12.4K Likes

Francesca Pallopides: Many users of hearing aids already live in an ~AR soundscape where some signals are enhanced and many others are deliberately suppressed. If and when visual AR takes off, I expect visual noise suppression to be a major basal function.

Francesca Pallopides: I’ve long predicted AR tech will be used to *reduce* the perceived complexity of the real world at least as much as it adds on extra layers. Most people will not want to live like in this video.

Augmented reality is a great idea, but simplicity is key. So is curation. You want the things you want when you want them. I don’t think I’d go as far as Francesca, but yes I would expect a lot of what high level AR does is to filter out stimuli you do not want, especially advertising. The additions that are not brought up on demand should mostly be modest, quiet and non-intrusive.

Quickly, There’s No Time

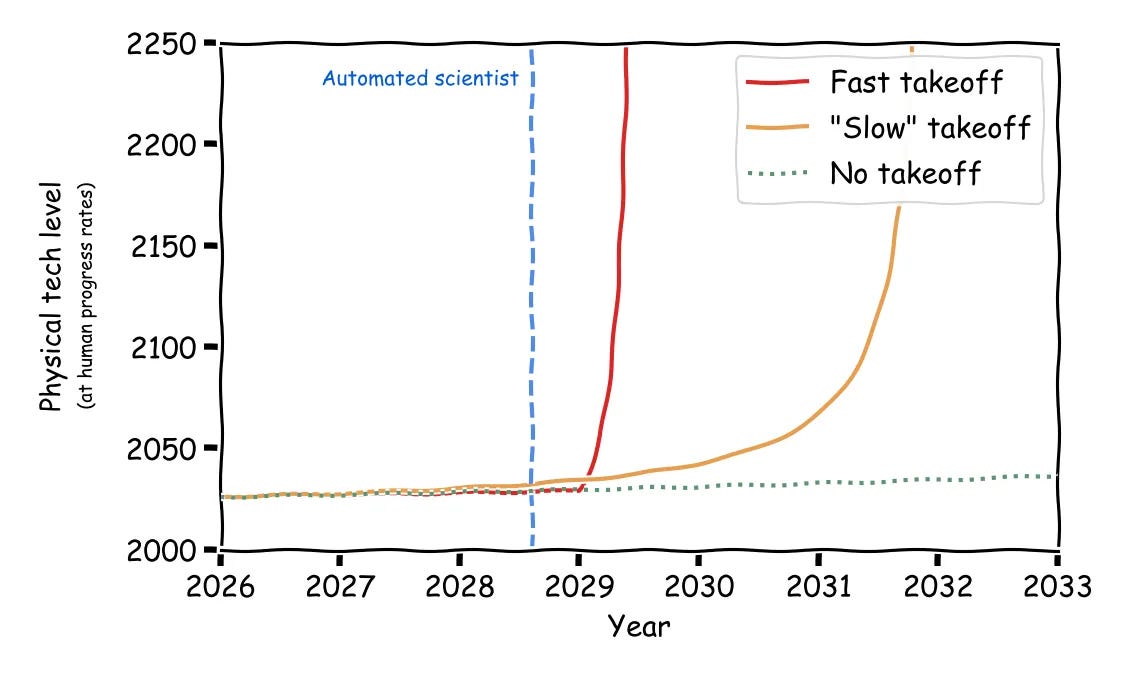

Ajeya Cotra makes the latest attempt to explain how a lot of disagreements about existential risk and other AI things still boil down to timelines and takeoff expectations.

If we get the green line, we’re essentially safe, but that would require things to stall out relatively soon. The yellow line is more hopeful than the red one, but scary as hell.

Is it possible to steer scientific development or are we ‘stuck with the tech tree?’

Tao Burga takes the stand that human agency can still matter, and that we often have intentionally reached for better branches, or better branches first, and had that make a big difference. I strongly agree.

We’ve now gone from ‘super short’ timelines of things like AI 2027 (as in, AGI and takeoff could start as soon as 2027) to ‘long’ timelines (as in, don’t worry, AGI won’t happen until 2035, so those people talking about 2027 were crazy), to now many rumors of (depending on how you count) 1-3 years.

Phil Metzger: Rumors I’m hearing from people working on frontier models is that AGI is later this year, while AI hard-takeoff is just 2-3 years away.

I meant people in the industry confiding what they think is about to happen. Not [the Dario] interview.

Austen Allred: Every single person I talk to working in advanced research at frontier model companies feels this way, and they’re people I know well enough to know they’re not bluffing.

They could be wrong or biased or blind due to their own incentives, but they’re not bluffing.

jason: heard the same whispers from folks in the trenches, they’re legit convinced we’re months not years away from agi, but man i remember when everyone said full self driving was just around the corner too

What caused this?

Basically nothing you shouldn’t have expected.

The move to the ‘long’ timelines was based on things as stupid as ‘this is what they call GPT-5 and it’s not that impressive.’

The move to the new ‘short’ timelines is based on, presumably, Opus 4.6 and Codex 5.3 and Claude Code catching fire and OpenClaw so on, and I’d say Opus 4.5 and Opus 4.6 exceeded expectations but none of that should have been especially surprising either.

We’re probably going to see the same people move around a bunch in response to more mostly unsurprising developments.

What happened with Bio Anchors? This was a famous-at-the-time timeline projection paper from Ajeya Cotra, based around the idea that AGI would take similar compute to what it took evolution, predicting AGI around 2050. Scott Alexander breaks it down, and the overall model holds up surprisingly well except it dramatically underestimated the rate algorithmic efficiency improvements, and if you adjust that you get a prediction of 2030.

If Anyone Builds It, We Can Avoid Building The Other It And Not Die

Saying ‘you would pause if you could’ is the kind of thing that gets people labeled with the slur ‘doomers’ and otherwise viciously attacked by exactly people like Alex Karp.

Instead Alex Karp is joining Demis Hassabis and Dario Amodei in essentially screaming for help with a coordination mechanism, whether he realizes it or not.

If anything he is taking a more aggressive pro-pause position than I do.

Jawwwn: Palantir CEO Alex Karp: The luddites arguing we should pause AI development are not living in reality and are de facto saying we should let our enemies win:

“If we didn’t have adversaries, I would be very in favor of pausing this technology completely, but we do.”

David Manheim: This was the argument that “realists” made against the biological weapons convention, the chemical weapons convention, the nuclear test ban treaty, and so on.

It’s self-fulfilling – if you decide reality doesn’t allow cooperation to prevent disasters, you won’t get cooperation.

Peter Wildeford: Wow. Palantir CEO -> “If we didn’t have adversaries, I would be very in favor of pausing this technology completely, but we do.”

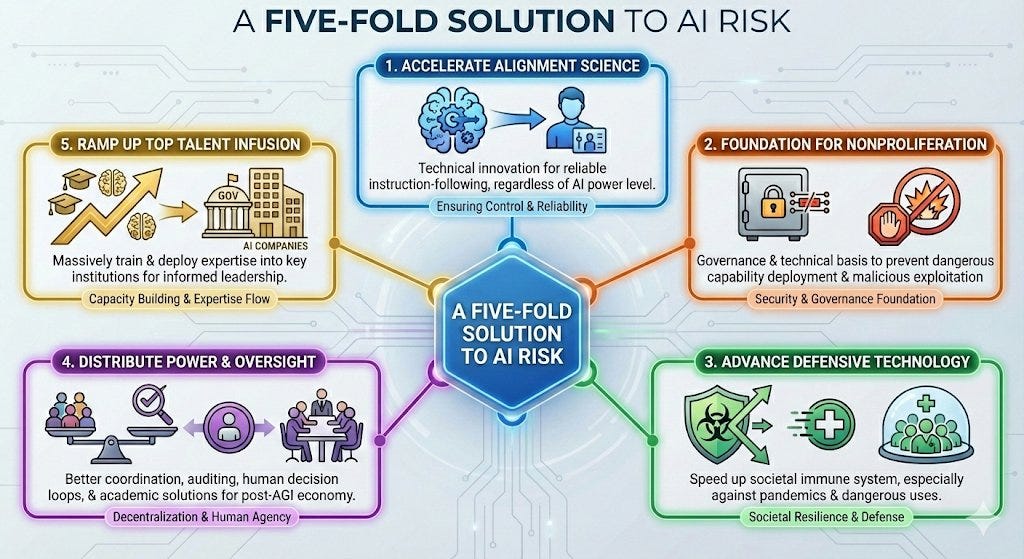

I agree that having adversaries makes pausing hard – this is why we need to build verification technology so we have the optionality to make a deal.

We should all be able to agree that a pause requires:

- An international agreement to pause.

- A sufficiently advanced verification or other enforcement mechanism.

Thus, we should clearly work on both of these things, as the costs of doing so are trivial compared to the option value we get if we can achieve them both.

In Other AI News

Anthropic adds Chris Liddell to its board of directors, bringing lots of corporate experience and also his prior role as Deputy White House Chief of Staff during Trump’s first term. Presumably this is a peace offering of sorts to both the market and White House.

India joins Pax Silica, the Trump administration’s effort to secure the global silicon supply chain. Other core members are Japan, South Korea, Singapore, the Netherlands, Israel, the UK, Australia, Qatar and the UAE. I am happy to have India onboard, but I am deeply skeptical of the level of status given here to Qatar and the UAE, when as far as I can tell they are only customers (and I have misgivings about how we deal with that aspect as well, including how we got to those agreements). Among others missing, Taiwan is not yet on that list. Taiwan is arguably the most important country in this supply chain.

GPT-5.2 derives a new result in theoretical physics.

OpenAI is also participating in the ‘1st Proof’ challenge.

Dario Amodei and Sam Altman conspicuously decline to hold hands or make eye contact during a photo op at the AI Summit in India.

Anthropic opens an office in Bengaluru, India, its second in Asia after Tokyo.

Anthropic announces partnership with Rwanda for healthcare and education.

AI Futures gives the December 2025 update on how their thinking and predictions have evolved over time, how the predictions work, and how our current world lines up against the predicted world of AI 2027.

Daniel Kokotajlo: The primary question we estimate an answer to is: How fast is AI progress moving relative to the AI 2027 scenario?

Our estimate: In aggregate, progress on quantitative metrics is at (very roughly) 65% of the pace that happens in AI 2027. Most qualitative predictions are on pace.

In other words: Like we said before, things are roughly on track, but progressing a bit slower.

OpenAI ‘accuses’ DeepSeek of distilling American models to ‘gain an edge.’ Well, yes, obviously they are doing this, I thought we all knew that? Them’s the rules.

MIRI’s Nate Sores went to the Munich Security Conference full of generals and senators to talk about existential risk from AI, and shares some of his logistical mishaps and also his remarks. It’s great that he was invited to speak, wasn’t laughed at and many praised him and also the book If Anyone Builds It, Everyone Dies. Unfortunately all the public talk was mild and pretended superintelligence was not going to be a thing. We have a long way to go.

If you let two AIs talk to each other for a while, what happens? You end up in an ‘attractor state.’ Groks will talk weird pseudo-words in all caps, GPT-5.2 will build stuff but then get stuck in a loop, and so on. It’s all weird and fun. I’m not sure what we can learn from it.

India is hosting the latest AI Summit, and like everyone else is treating it primarily as a business opportunity to attract investment. The post also covers India’s AI regulations, which are light touch and mostly rely on their existing law. Given how overregulated I believe India is in general, ‘our existing laws can handle it’ and worry about further overregulation and botched implementation have relatively strong cases there.

Introducing

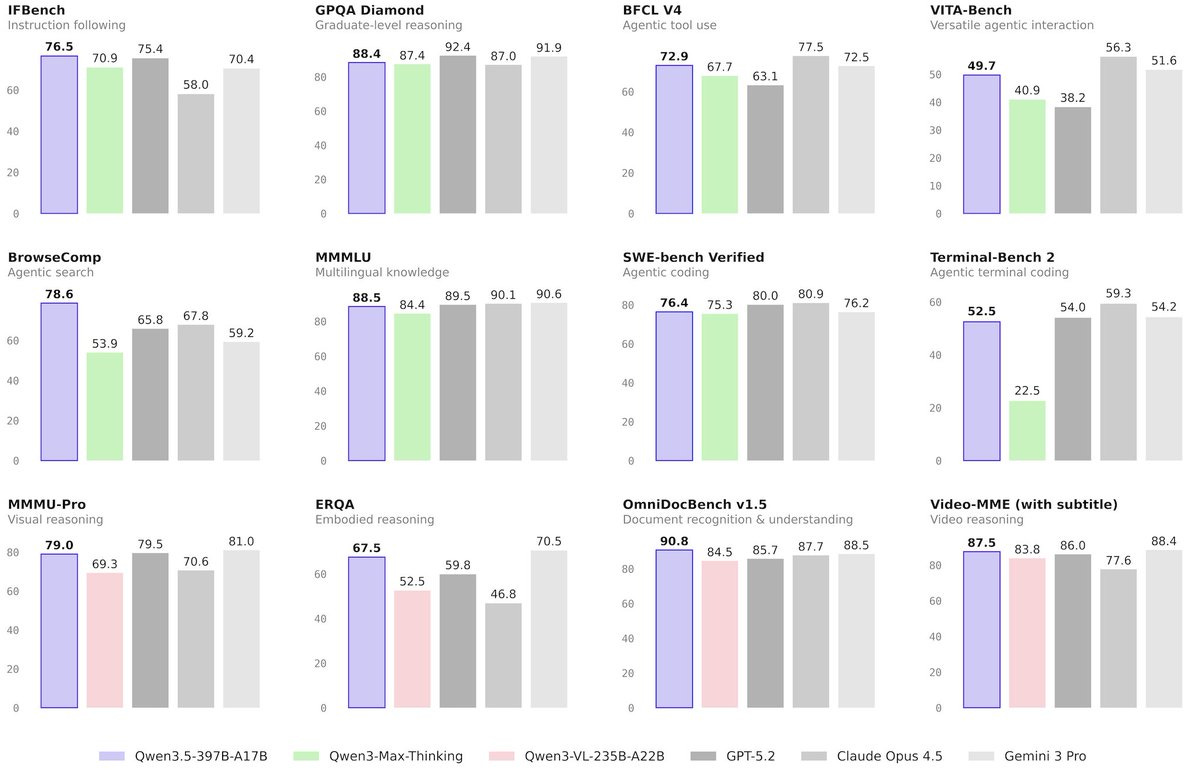

Qwen 3.5-397B-A17B, HuggingFace here, 1M context window.

We have some benchmarks.

Tiny Aya, a family of massively multilingual models that can fit on phones.

Get Involved

Tyler John has compiled a plan for a philanthropic strategy for the AGI transition called The Foundation Layer, and he is hiring.

Tyler’s effort is a lot like Bengio’s State of AI report. It describes all the facts in a fashion engineered to be calm and respectable. The fact that by default we are all going to die is there, but if you don’t want to notice it you can avoid noticing it.

There are rooms where this is your only move, so I get it, but I don’t love it.

Tyler John: The core argument?

The best available evidence based on benchmarks, expert testimony, and long-term trends imply that we should expect smarter-than-human AI around 2030. Once we achieve this: billions of superhuman AIs deployed everywhere.

This leads to 3 major risks:

- AI will distribute + invent dual-use technologies like bioweapons and dirty bombs

- If we can’t reliably control them, and we automate most of human decision-making, AI takes over

- If we can control them, a small group of people can rule the world

Society is rushing to give AI control of companies, government decision-making, and military command and control. Meanwhile AI systems disable oversight mechanisms in testing, lie to users to pursue their own goals, and adopt misaligned personas like Sydney and Mecha Hitler.

I may sound like a doomer, but relative to many people who understand AI I am actually an optimist, because I think these problems can be solved. But with many technologies, we can fix problems gradually over decades. Here, we may have just five years.

I advocate philanthropy as a solution. Unlike markets, philanthropy can be laser focused on the most important problems and act to prepare us before capital incentives exist. Unlike governments, philanthropy can deploy rapidly at scale and be unconstrained by bureaucracy.

I estimate that foundations and nonprofit organizations have had an impact on AGI safety comparable to any AI lab or government, for about 1/1,000th of the cost of OpenAI’s Project Stargate.

Want to get started? Look no further than Appendix A for a list of advisors who can help you on your journey, co-funders who can come alongside you, and funds for a more hands-off approach. Or email me at tyler@foundation-layer.ai

Blue Rose is hiring an AI Politics Fellow.

Show Me the Money

Anthropic raises $30 billion at $380 billion post-money valuation, a small fraction of the value it has recently wiped off the stock market, in the totally normal Series G, so only 19 series left to go. That number seems low to me, given what has happened in the last few months with Opus 4.5, Opus 4.6 and Claude Code.

andy jones: i am glad this chart is public now because it is bananas. it is ridiculous. it should not exist.

it should be taken less as evidence about anthropic’s execution or potential and more as evidence about how weird the world we’ve found ourselves in is.

Tim Duffy: This one is a shock to me. I expected the revenue growth rate to slow a bit this year, but y’all are already up 50% from end of 2025!?!!?!

Investment in AI is accelerating to north of $1 trillion a year.

The Week In Audio

Trailer for ‘The AI Doc: Or How I Became An Apocaloptimist,’ movie out March 27. Several people who were interviewed or involved have given it high praise as a fair and balanced presentation.

Ross Douthat interviews Dario Amodei.

Y Combinator podcast hosts Boris Cherny, creator of Claude Code.

Ajeya Cotra on 80,000 Hours.

Tomorrow we continue with Part 2.

Genre and Era: Lead with a specific genre, a unique mix, or a musical era.

Genre and Era: Lead with a specific genre, a unique mix, or a musical era. Tempo and Rhythm: Set the energy and describe how the beat feels.

Tempo and Rhythm: Set the energy and describe how the beat feels. Instruments: Ask for specific sounds or solos to add texture to your track.

Instruments: Ask for specific sounds or solos to add texture to your track. Vocals: Specify gender, voice texture (timbre), and range for the best delivery.

Vocals: Specify gender, voice texture (timbre), and range for the best delivery. Lyrics: Describe the topic, include personalized details, or provide your own text with structure tags.

Lyrics: Describe the topic, include personalized details, or provide your own text with structure tags. Photos or Videos (Optional): If you want to give Gemini even more context for your track, try uploading a reference image or video to the prompt.

Photos or Videos (Optional): If you want to give Gemini even more context for your track, try uploading a reference image or video to the prompt.

@AutismCapital

@AutismCapital