H5N1—also known as bird flu—continues to spread among animals and, for the first time, is spreading among cows. Thankfully, the risk to the public is low, but the more the virus spreads, the more chances it has to mutate and jump species to spread among humans. Given H5N1’s high mortality rate, we don’t want this to happen.

This outbreak is concerning; unfortunately, communication and data transparency have been profoundly lacking. We must do better and faster — repeating the same communication mistakes that fueled confusion, distrust, and misinformation during Covid-19 is inexcusable.

Here’s what we do and don’t know about H5N1.

This post builds off previous YLE updates of the current cow outbreak. To get up to speed, start here.

H5N1 continues to spread among animals

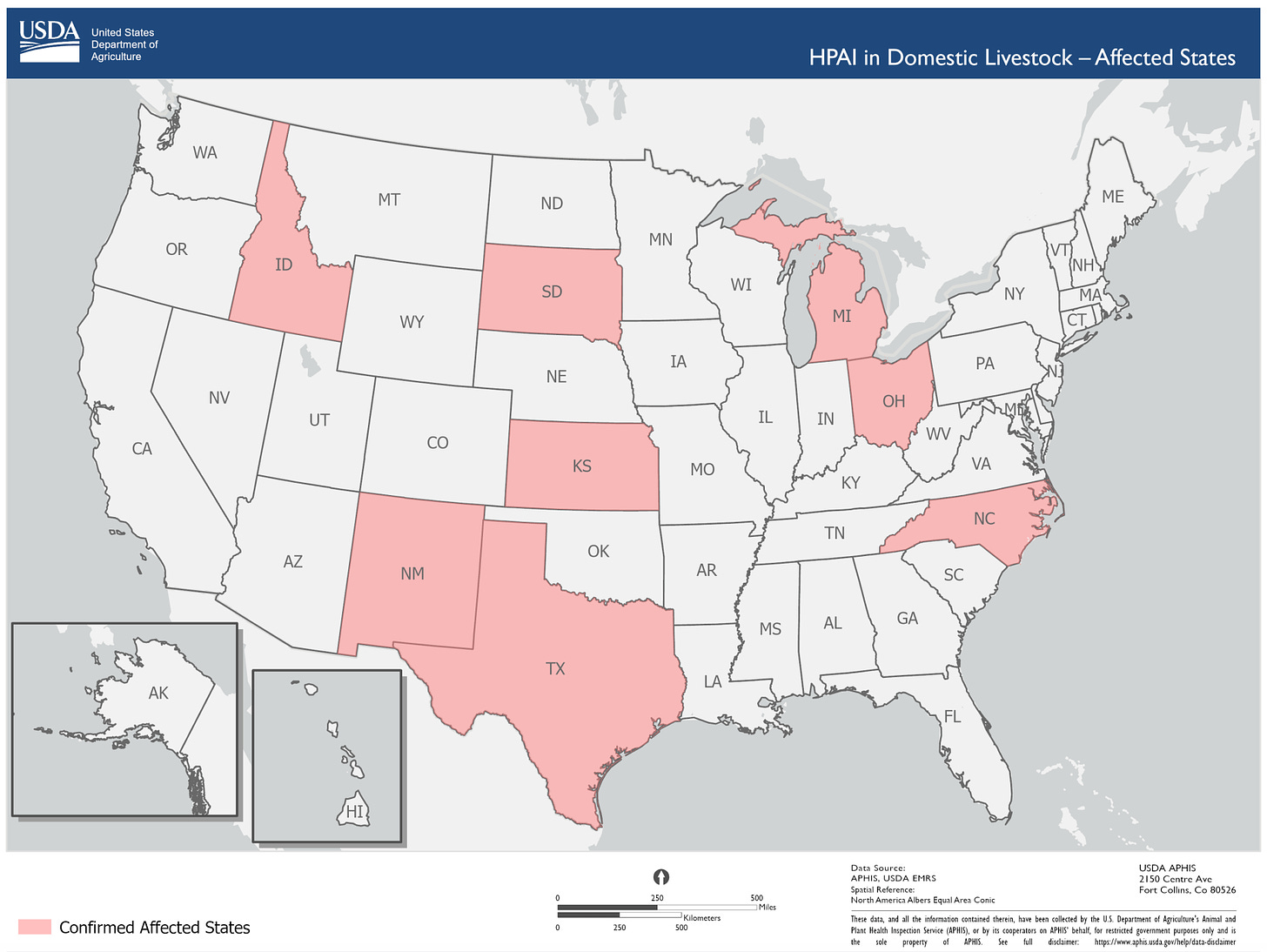

H5N1 been detected among 33 dairy cattle herds in 8 states. The virus is spreading through multiple known pathways: wild bird → cow; cow → cow; cow → poultry, and once from cow → human. Thankfully, there is currently no evidence of human-to-human transmission.

How big is the “true” outbreak? We don’t know. Symptomatic testing of animals and humans is voluntary, and asymptomatic testing is not happening (likely due to industry pressure), which means we are flying blind. It’s been reported that more workers have symptoms — such as fever, cough, and lethargy — but are unwilling to test. We could have more human cases. Among the tests conducted, it’s unclear how many have been done, how many were positive, and how many humans have been exposed.

Two positive updates:

There is a federal rule for moving cows now. As of yesterday, the federal government requires testing all lactating cows before moving across states. Finally! Unfortunately, it’s likely too late to contain transmission.

Pigs have been testing negative. This is good news. Pigs are dangerous hosts for H5N1 because they have avian and human receptors. They are known as “mixing vessels” for influenza viruses.

The outbreak is much larger and started earlier than we thought.

We don’t know how big the outbreak is from physically swabbing animals and humans, but two clues suggest this has been spreading under our noses for a while:

Clue #1: The FDA found H5N1 fragments in the milk supply. This was surprising because milk from known infected cows was not going to the market. This confirms that the cow outbreak is bigger than previously known.

Thankfully, milk pasteurization should deactivate any bird flu that makes it into the milk supply. Scientists confirmed this yesterday: they could not grow active virus from the milk samples. This means the virus fragments detected in milk were broken pieces that cannot replicate and, thus, cannot harm humans. The FDA is testing more samples just in case. Thus far, the public has seen no data.

Clue #2: Genomic surveillance can tell us how, where, and when H5N1 mutates. After being reluctant to share genetic data, USDA finally shared 239 viral sequences from animal infections. However, the data was incomplete—the date and location of the sample collection were not included, making it difficult to answer key questions about how the virus has changed over time and, therefore, predict where it might end up.

Also, there was no mention of what USDA scientists found with this data internally. We’ve relied on scientists on social media to walk through what they found after analyzing the raw data, which suggests an estimated spillover to dairy cows starting in December.

Wastewater is spiking. Is it H5N1?

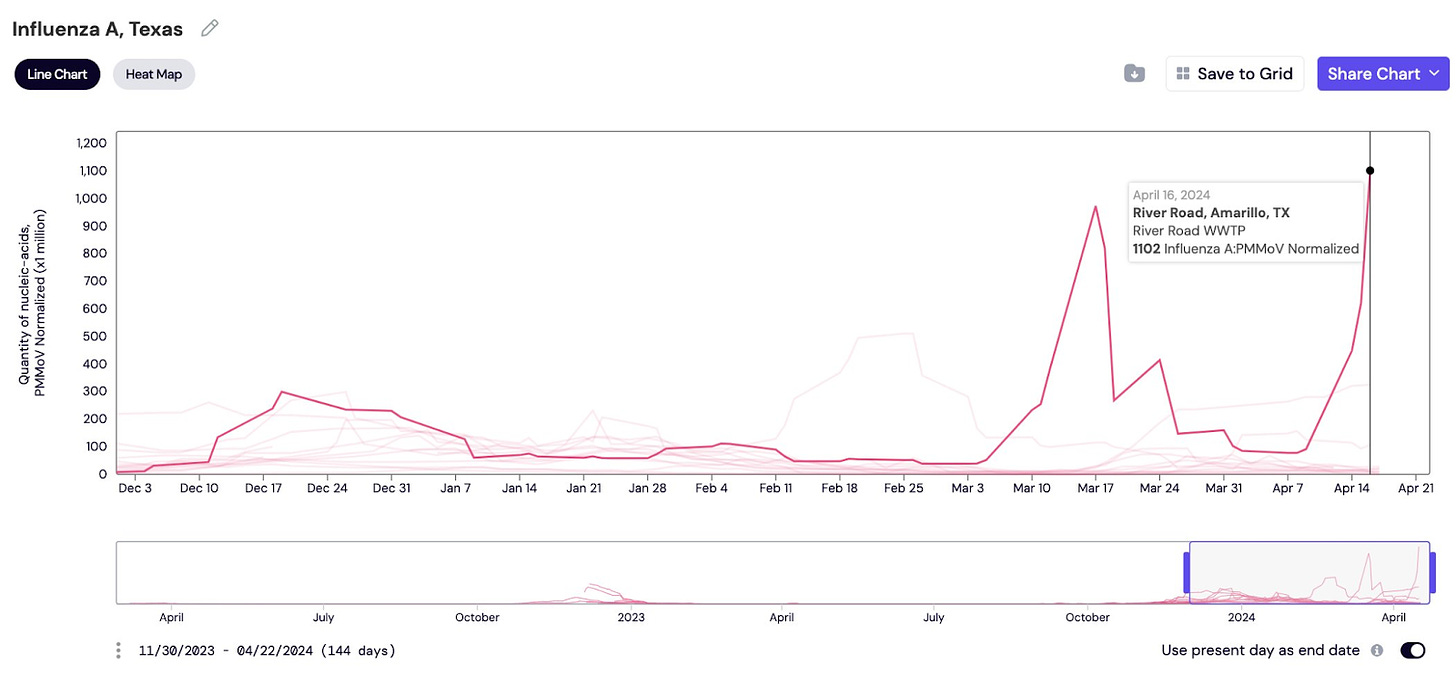

Some on social media discovered wastewater spiking in some places with infected herds. For example, in Amarillo, Texas, wastewater is skyrocketing for flu A while the rest of the state remains low.

Could this be H5N1? Yes, but we don’t know for sure; the government has not officially shared anything about wastewater. This is incredibly disappointing, given this is the perfect use case for wastewater monitoring.

While we don’t have a wastewater test for H5N1 yet, it has many similarities to flu strain A. Some wastewater systems include human wastewater and stormwater. Given that Amarillo has stockyards, this strengthens the possibility that it’s H5N1, especially since we aren’t seeing it in other parts of the state. The most likely scenario? The spike is from milk dumping or animal sewage. We need more data.

The tools work, but…

The U.S. government has confirmed that Tamiflu and the stockpiled H5N1 vaccines are predicted to have efficacy if this does move to humans. This is great news. And I agree there shouldn’t be panic. But I caution leaders against the “we’re fine, we have vaccines” attitude.

What about manufacturing and supply?

What about the rest of the globe?

What about vaccine hesitancy?

And decline in trust?

And access problems?

Of course, fully relying on vaccines and overconfidence were among the big mistakes of the Covid-19 emergency. As one of our colleagues wrote, “It’s best to face these threats with humility and determination.”

A communication void will be filled with confusion, mistrust, and misinformation

Information from the response has not been easy to find, has not been complete, and has not been backed with data, leaving many of us to piece together a fuzzy picture.

This is a big problem for many reasons:

Misinformation brews in information voids. People, rightfully so, have questions and can’t find answers.

Trusted messengers don’t know what’s going on. During an outbreak, top-down, credible, and consistent communication is necessary. Equally important is actively equipping trusted messengers—mass media, scientists, physicians, and community leaders—so they can communicate from the bottom up.

Tools could be at risk. For example, wastewater surveillance is one of the only tools that wasn’t weaponized during Covid-19 emergency. My biggest concern is that if we aren’t transparent—walking the public through what we are and are not doing with wastewater—people will become hesitant about this surveillance.

Chips away at credibility. Although brilliant scientists are within each agency, their expertise isn’t shining through.

Harming global capacity to respond. This is an emerging global pandemic threat. Other countries need to know, for example, if they should start testing their cows. If they should be looking for mutations, and where.

We need a coordinated response from our government. Yes, there are multiple players involved. And yes, they have their own priorities, legal authorities, agility, experience, and politics. However, honest, frequent, direct communication earns the public’s trust and confidence. If not, communities are starved for good information during outbreaks or emergencies, leading to unnecessary anxiety, confusion, and frustration.

After much pressure, government agencies finally hosted a live briefing for the media yesterday. This is a positive step in the right direction and, I hope, a sign that the winds are changing.

Bottom line

Responses need to get better faster. H5N1 is a dangerous disease that can affect our economy, food security, and animal and human health. This response has been incredibly difficult to watch on the heels of Covid-19 (and mpox and other emergencies like the East Palestine train accident). We get just so many “practice runs” before it starts costing lives again.

Love, YLE and Dr. P

“Your Local Epidemiologist (YLE)” is written and founded by Dr. Katelyn Jetelina, M.P.H. Ph.D.—an epidemiologist, wife, and mom of two little girls. During the day, she is a senior scientific consultant to several organizations, including CDC. At night, she writes this newsletter. Her main goal is to “translate” the ever-evolving public health world so that people will be well-equipped to make evidence-based decisions. This newsletter is free, thanks to the generous support of fellow YLE community members. To support this effort, subscribe below:

Kristen Panthagani, MD, PhD, is a resident physician and Yale Emergency Scholar, completing a combined Emergency Medicine residency and research fellowship focusing on health literacy and communication. You can find her on Threads, Instagram, or subscribe to her website here. Views expressed belong to Dr. P, not her employer.